I want to tell a story.

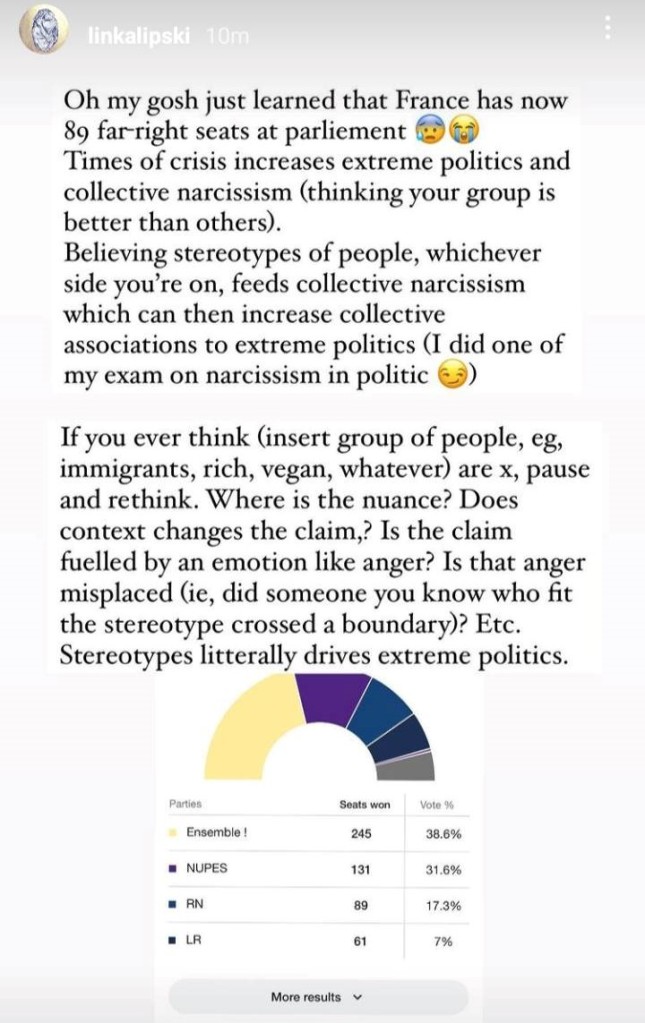

In 2015, French journalists publish three books asserting that the famous 20th century architect Le Corbusier was a Fascist (seen HERE): A Corbusier, by Francois Chaslin; Le Corbusier: A Cold Vision of the World, by Marc Perelman; and A French Fascism, by Xavier de Jarcy. These journalists’ books amount to a protest against a new Corbusier Museum and advocate for a statue of him in Poissy France – the location of probably his most famous building – to be razed. Though these works apparently generate a fair bit of public discussion in France, I don’t learn about them until 2022. I am intrigued and curious. Who is Le Corbusier, you may be asking? I’ll get to that. Notably, as of June, 2022, the far right held 17.3% of France’s parliament seats.

In 2001, two planes flown by Islamic extremists fly into the World Trade Center Towers in New York City, and the world changes. The US responds with “Shock and Awe” and a twenty year war in Afghanistan. This leads to a massive rise in extremism and war in the Middle East, followed by multiple, uncontrollable waves of immigration to Europe and, to a lesser extent, the US.

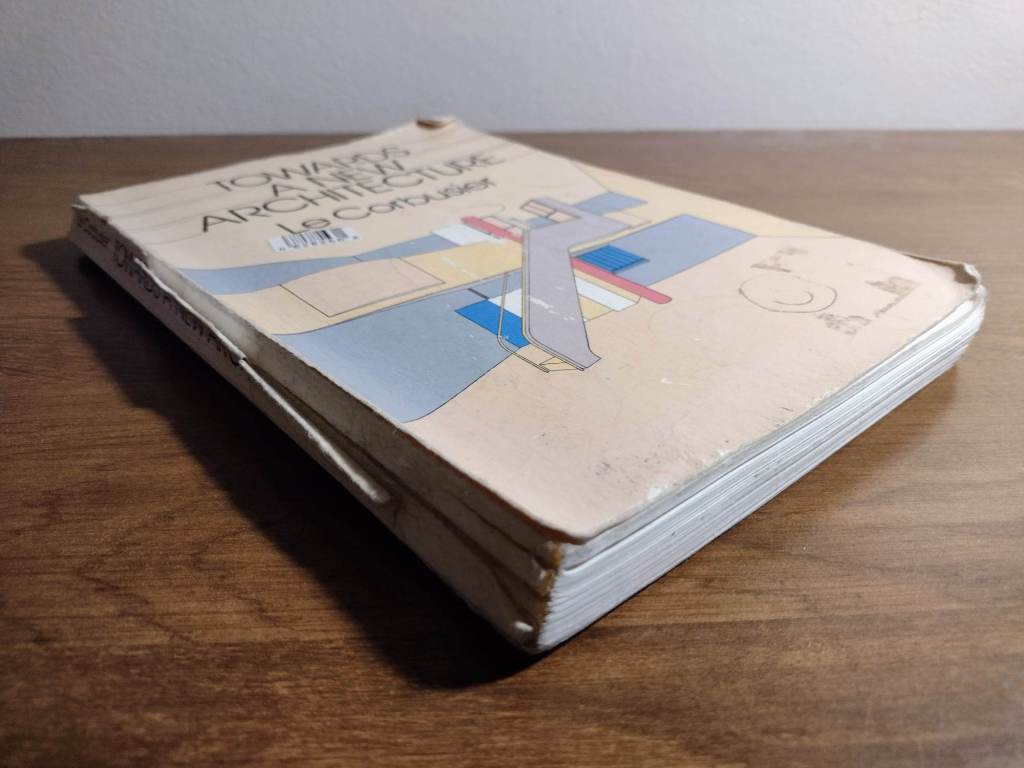

I start Architecture school at Virginia Tech in 1997 and read Towards A New Architecture, by Le Corbusier. I am enthralled, floored, and inspired. My curiosity is piqued, and to say I dive in and study it in detail throughout my time in Architecture school and beyond is a vast understatement. To give an idea of what I mean, this is my copy of it:

The story I want to tell is partly a personal story.

In the Fall of 2000, I travel around Europe to study Architecture and have the opportunity to encounter some of Corbusier’s works in person.

When I am eight years old, and ten years before I later start Architecture school, the Centre Pompidou in Paris has an exhibition on Corbusier’s ties to Fascism. This is 1987. It particularly highlights Corbusier’s work with the Vichy Regime in 1940 and ’41. The amount of publicity and hoopla this exhibition garners is such that I never learn about it until just recently (2022). The amount of new scholarship in the books published in 2015 that wasn’t available or known either in 1987 or while I was in Architecture school is minimal.

Le Corbusier practices architecture from 1905 until his death in 1965. The most famous building of his early period is completed in 1929 – as noted above, in Poissy, France. After WWII, his work changes dramatically. In what ways did it change, and what were the common threads throughout? I’ll get to that, but – speaking of “the world changed with 9/11” – the basic idea is oriented around an energetic optimism in building the modern world that seems to have been a global vision chastened with the failures presented by war at a global scale.

The story I want to tell is partly a story of global politics.

In 1887, Le Corbusier is born in Switzerland. This is to say that he was raised in an environment dominated by a universalizing, bourgeoisie cosmopolitanism centered in and radiating from France. Just to his North, the fermenting reaction was a German Nationalism that tended to characterize what spread from France as a vain, arbitrary, placelessness.

The story I want to tell is also partly a story about stories.

What presents us here with the opportunity to tell a story about stories is the relationship between, on the one hand, Corbusier’s architectural work and, on the other, the stories people tell about it. Besides asserting that Le Corbusier was a Fascist, what stories have people told about him and his work? He claimed at one point to be a Socialist, by the way. I will get to that.

In the meantime, and in order to do what I want to do, I also need to give my uninitiated reader a picture of what Corbusier’s work is about. Here is a brief video that serves as a very good introduction to him and his work and sets them in the larger context of our socio-political history:

There are a couple points of clarification that need to be made on that otherwise very good and informative presentation, because they are directly relevant to two of the elements of Corbusier’s work that I want to draw out moving forward – namely: the relationship with the body, and the totalizing vision of modernity. These are two of a number of aspects of his work – and their larger place in the tradition of Architecture – that most clearly and obviously speak to our political questions. To address the body, Corbusier never said his city planning should be “more Cartesian” (5:42 of video). Also, the video implied a significant conceptual break between said city planning and architecture. Corbusier never did that. His vision wasn’t limited to a commissioned building, because he was intentionally and actively seeking to shape society.

Besides the fact that Corbusier’s works – and their larger contextual references in our architectural tradition – are communal projects aimed at ways of life together, these and other ways they speak to our ideological questions of Corbusier’s Fascism will become more clear later. Each aspect of his work that I want to tell stories about articulates or reveals elements of our larger environment that we tend not to notice. Why do we tend not to notice them? We take them for granted as “just the way things are.” One thing they reveal, however, is that, much like the stories we tell, they are actually constructs of our own making. Seeing our construction at work through the course of our architectural history thus helps us to potentially see what we might otherwise not.

Like I said, I want to tell a story about stories. So, as I move through what Corbusier was doing in his work, I ask that my reader keep some questions in the forefront of the mind. Was Corbusier making ideological assertions? For example, where he presents a particular image of the body, was he prescribing or describing? Was he making assertions, or was he reconciling to the reality of the conditions with which he was presented? Was he making a statement about what he believes “should” be, or was he articulating what it means for something to appear in the world in the first place? Where and in what particular ways was he articulating or asserting, and where was he observing and reconciling?

So, I am telling a story about some French journalists writing a book. I am telling a story about a famous French architect named Le Corbusier, about whom the French journalists wrote books. This is partly a personal story, and partly a story of global, national, and local politics. It’s a story of stories, in that it’s a story about stories being told. But, it’s also a story of stories in that the stories being told contain stories within stories. Here begins one of those stories within stories. What better place to start than the ground?

This monastery was built in the 6th century AD, at the foot of Mt. Sinai, otherwise known as Mt. Horeb, or Mt. Hermon. Though this is the mountain where Moses is said to have received the 10 Commandments, that is not the story I want to tell here. Instead, this is a story of the joint between building and earth. See and observe how the builders made specific decisions of how to raise materials upon the earth, at a very limited, local scale, in response to the actual changes in terrain below and before them. Where the terrain changes, so does the place where building meets and stands up upon earth. And, the human person moves along the undulating terrain with the buildings.

Seen here is the central plaza of Medieval Siena, Italy. Tuscany is known for its hills, but here, effort was aimed towards a large, open plaza. The buildings and the people move along the earth’s terrain. In this sense, what happens is like St. Catherine’s Monastery, except earth is covered over with paving stones, and the space is opened up for breathing and for getting a wider view of things.

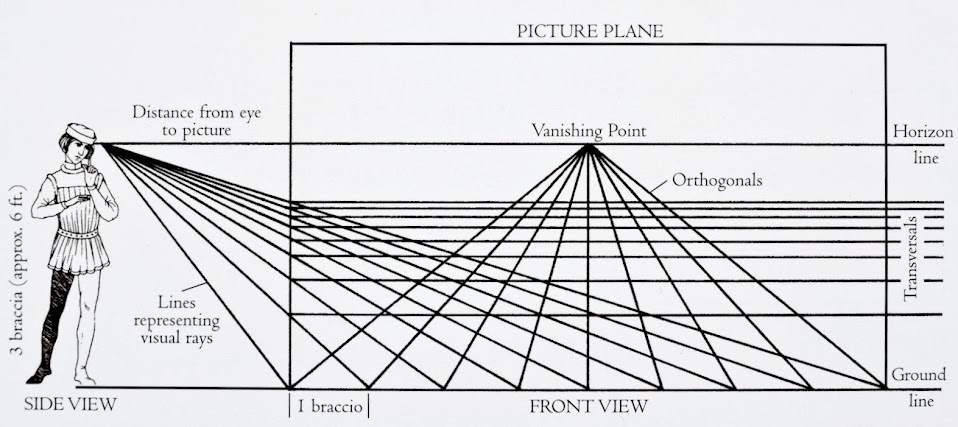

This is an illustration of Renaissance painter and architect Alberti’s geometric construction aimed towards imitating nature’s optical laws of perspective. Of note, this is explicitly a construction. This is not an image of what or how we actually see but, rather, a conscious approximation of what happens under an ideal set of controlled conditions – such as in a large, open, Italian plaza. Notably, perspective was invented in Tuscany, by Filippo Brunelleschi, in 1404. Remember that Tuscany is known for its hills. Note here that the ground line is perfectly flat and horizontal. The “picture plane” could be said to be a good image of how we interpretively “frame” reality. As I said, I am here partly telling a story about stories.

Where and in what particular ways was Corbusier here articulating or asserting how to build, and where was he observing and reconciling how modern people perceive and interpret reality?

Remember that “the ground” is an artificial construct that we take for granted in our language as “just the way things are” but which is built as such into our actual history. Where and in what particular ways are assertions being made here, as compared to making observations and reconciling to actual, concrete reality? Are specific “building” decisions being made at local points along the terrain before and below us, or are these grand, ideological gestures aimed towards a wider view of things, itself built upon stones paved by past generations?

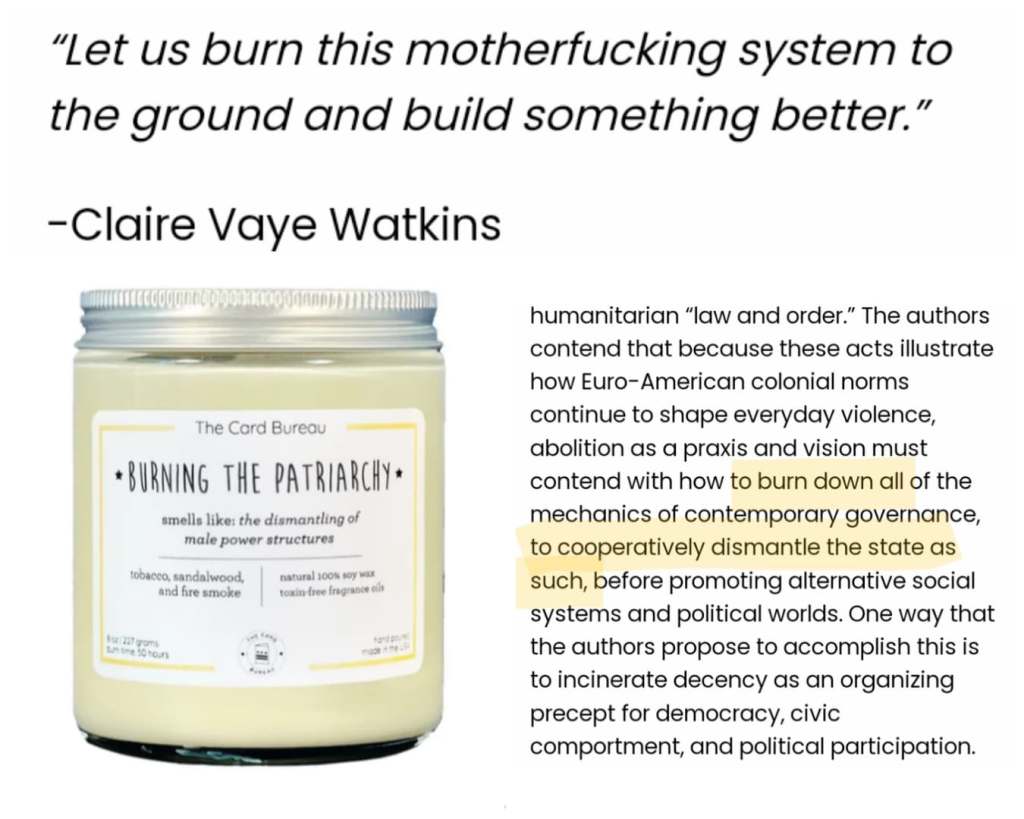

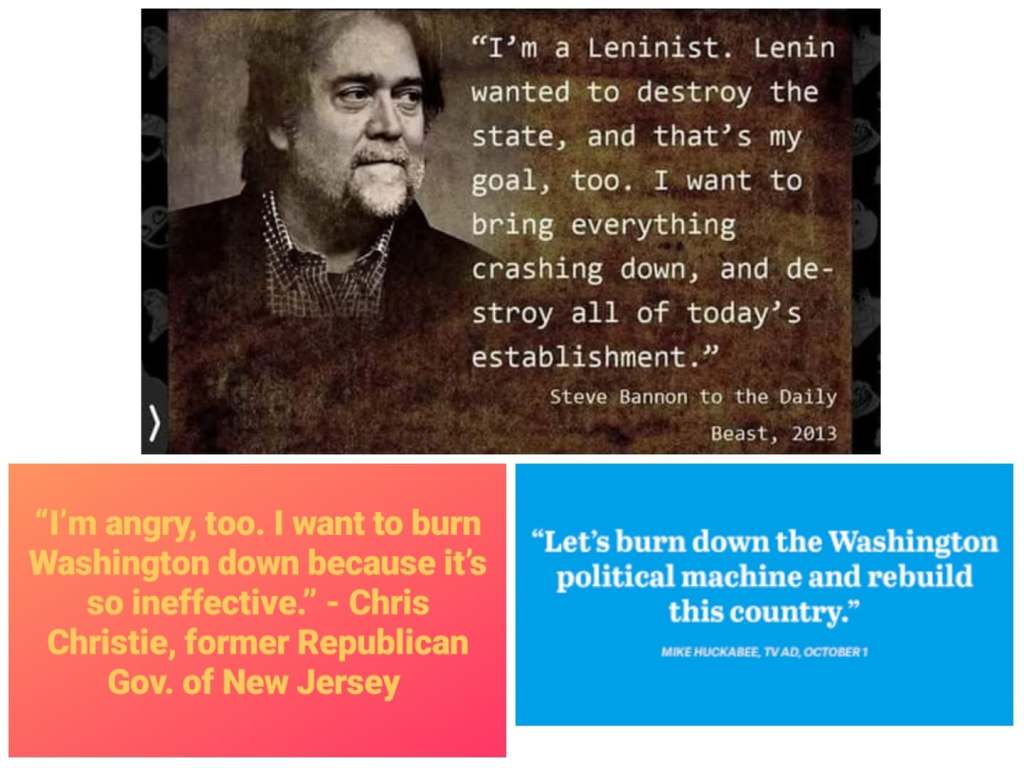

These conservatives don’t explicitly state that they want to burn it all down “to the ground,” but that’s the unstated implication. Obviously, people who sit on both sides of the political aisle “walk on the ground,” right? One might object that “burning it all down to the ground” is merely is a figure of speech, but so is the “building back up again” upon it. We could only presume for our work of critique to reach as far as “the ground” if we construct said ground in the first place. That’s why St. Catherine’s Monastery is instructive. We don’t construct either the earth or the mountain upon which the monastery is elevated. We all inhabit the history of our art and architecture, whether we realize it or not, whether we commit to the left or to the right.

The question of whether Corbusier was actually a Fascist remains, but have we begun to get a sense of why it’s an intriguing and important question? There are a number of other stories within stories to tell to get a better and more full sense of it.

Pingback: WAS LE CORBUSIER A FASCIST? Moving Around the Question | Knowing God

Pingback: WAS LE CORBUSIER A FASCIST? The Body of the Question | Knowing God

Pingback: WAS LE CORBUSIER A FASCIST? The Governance of the Question | Knowing God

Pingback: WAS LE CORBUSIER A FASCIST? The Mechanics of the Question | Knowing God

Pingback: WAS LE CORBUSIER A FASCIST? The Structure of the Question | Knowing God

Pingback: WAS LE CORBUSIER A FASCIST? The Land Where The Question Is Heard | Knowing God

Pingback: WAS LE CORBUSIER A FASCIST? The Mystery of the Question | Knowing God

Pingback: WAS LE CORBUSIER A FASCIST? Well, Yes, But… | Knowing God

Pingback: WAS LE CORBUSIER A FASCIST? A Question of Assertion or Play? | Knowing God

Pingback: WAS LE CORBUSIER A FASCIST? Our Current Common Conditions | Knowing God

Pingback: WAS LE CORBUSIER A FASCIST? Conclusion and Index | Knowing God