In my previous posts – links HERE, HERE, HERE, HERE, and HERE – I was telling a story. It is a story about stories, in that it was prompted by three French journalists telling us a story – namely, that the famous 20th century architect Le Corbusier was a Fascist. It is a personal story, in that I am repulsed by fascism but love Le Corbusier. It is a geo-political story, in that Corbusier was born and raised, quite actually, right in the middle space between French cosmopolitanism and German Nationalism. It is also, of course, a story, about Le Corbusier and his work. And, it is a story with multiple other stories folded up inside a story. I have told a few of those stories inside a story, which hopefully began to give a sense of why this blog series carries its title. Now I want to continue to tell more of those.

Two posts back, I told a story of the “governance,” or “regulation” of what appears. This is a story of the structure of what appears. How does what appears hold together?

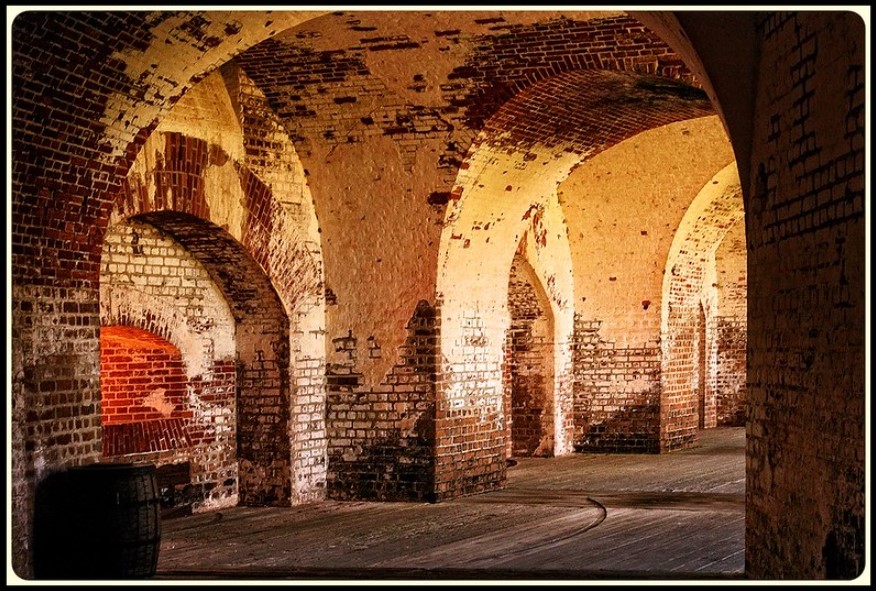

At Fort Pulaski, the weight of the building is carried to the earth in what we would now term “compression.” In language more native to the craft of the masonry by which such buildings were made, we can say the elements of the building were woven together like a communal fabric. My reader can get more of a sense of how this works HERE, HERE, and HERE. If the building is held together like a communal fabric, we could say it appears as an analogy to the community it houses and locates. We can then begin to see that and how such a community is held together as a “fabric” in just the same way. Without one part, the whole falls down, falls apart, or no longer appears and functions as what it is meant to.

Every community has conflict, whether within or without. Ancients sacrificed enemies to make this communal fabric appear. Aztecs lived in one community, and Mayans lived in another. Where conflict arose, and Aztecs were victorious, the Aztec figurehead, the priest, for the life of the Aztec community, sacrificed and took into himself the lifeblood of the Mayan enemy. The Roman Empire occupied the Jewish Promised Land. The one who claimed to be the true heir of the Jewish throne was sacrificed to the lifeblood of Rome, in order to hold the socio-political fabric of Rome intact as such.

Notice that the structure of Fort Pulaski itself – the architectural language of the arches, openings and closings, windows and walls, lights and shadows, figures and directions – tells an embodied and symbolic story of the relationship between heaven and earth. The fabric of an ancient community was imagined to be interwoven with that of the cosmos.

When the imagined location from which we understand reality comes to be located in outer space (see previous post on our relationship with space, HERE), human dwelling is no longer thought to be a union of the two. When bodies appear as objects at a speculative distance in space rather than as participants in the embodied weaving of the socio-political and cosmological fabric (see previous post on the body, HERE), observed space between heaven and earth also becomes a spectacle. Rather than joined through the weaving of a fabric, heaven and earth appear to be in tension with one another.

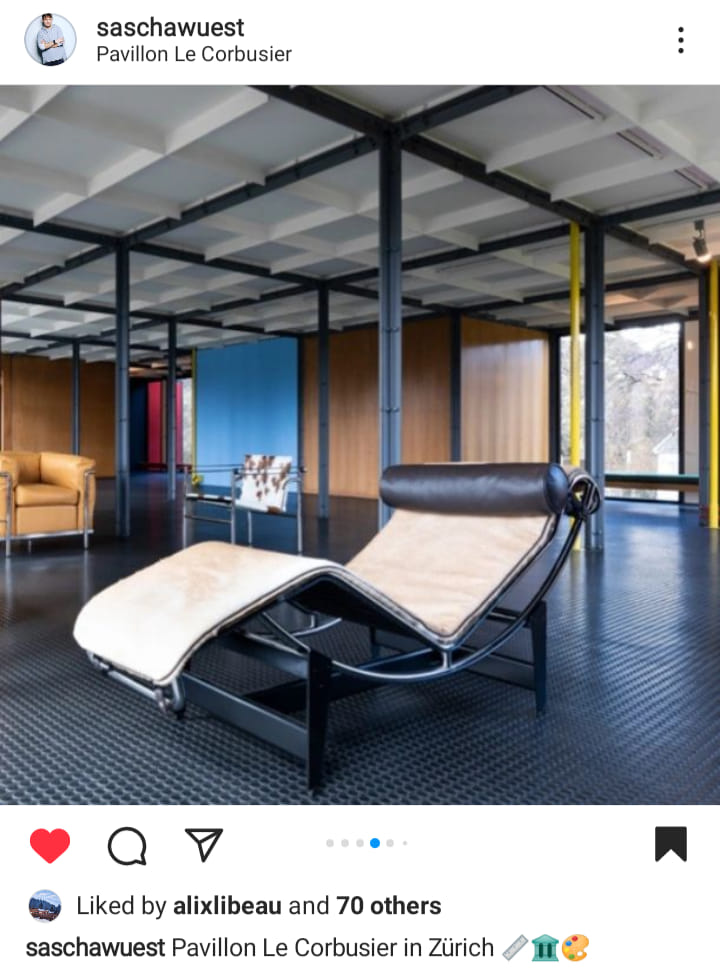

So, we see that, unlike an ancient building, a modern building is held together in tension. These individual posts are held together by bolts, which are in tension. The bolted-together angle bars that are functioning as beams are, themselves, mostly in tension. Notably, Le Corbusier’s concrete buildings appear to stand in compression but are actually largely held together by rebar inside the concrete, which is in tension. And – as poetically symbolized at Villa Savoye and discussed previously HERE – see again the absent body floating above the ground horizontally (the recliner). In modernity, the tension between mind and body is the prime movement by which we can see and know other movements.

Though the body’s senses are bound to what appears inside the horizon, the mind is not so limited (see Aquinas’ Summa Theologica). The ends of these bolts holding the posts in tension are right next to each other, but they are really at two poles of the entire globe. The poles between which modern society’s tensions pull are always essentially as far apart as the breadth of the earth itself. The universality of the nature of the act of pulling the universe apart testifies to this:

“Liberalism…permeates our minds and affects our attitude towards much of life. That Liberalism may be a tendency towards something very different from itself, is a possibility in its nature. For it is something which tends to release energy rather than accumulate it, to relax, rather than to fortify. It is a movement not so much defined by its end, as by its starting point; away from, rather than towards, something definite. Our point of departure is more real to us than our destination; and the destination is likely to present a very different picture when arrived at, from the vaguer image formed in imagination…I am concerned with a state of mind which, in certain circumstances, can become universal and infect opponents as well as defenders.”

– T.S. Eliot, Christianity and Culture, pp. 12-13

Modern Aztecs and Mayans, so to speak, do not and can never occupy different territories. Liberals and conservatives always take up the same territory, which is always spatially total and extends far beyond the bounds of a sensed communal fabric. To quote T.S. Eliot in Christianity and Culture (p. 33), we live in “a community turned into a mob.”

Space occupied in a modern society is only understood in the mind. The “mind’s eye” is the location from which we have a view of our world. What is then left for moderns as a means of relating to the enemy is not embodied, sacrificial giving of lifeblood but, rather, the practice of discursive critique. In language native to the craft of modern, mechanized, industrial production (see previous post on machines, HERE), we can say that modern society holds together in the same way as the standardized, mass-produced building. So, we see that, unlike an ancient polity, a modern one is held together in tension. This tension takes the political form of ideological warfare.

In the sanctuary at Le Corbusier’s Monastery at La Tourette, are the various elements that appear held together at a tense distance from one another? Or, rather, does the altar of sacrifice serve as the center, by which all things come to appear a harmonious order together? Is Corbusier making an ideological assertion or describing and inhabiting an iconic image of our history?

In Corbusier’s writing and work, we see that, whatever the answer to that question, he is not immune to the way we, as moderns, are formed into a functional identity in ideological tension against our enemies.

Here is Le Corbusier critiquing the ineffectual, emotive romanticism of the predominantly elitist architectural schools of his day:

“[T]he world is unanimous in considering as gas-bags, shirkers, incapables, dull and hidebound characters, the one or two people who have grasped the lesson of primitive man in his glade, and who claim that there do exist such things as regulating lines: ‘With your regulating lines you kill imagination, you make a god of a recipe.’

– Le Corbusier, Towards A New Architecture, p. 73

‘But all earlier epochs have employed this necessary instrument.’ [Corbusier’s implied reply]

‘It is not true, you have invented it; you are a maniac.’ [says ‘the world’]

But the past has left us proofs, iconographical documents, steles, slabs, incised stones, parchments, manuscripts, printed matter….’”

“But he proclaims that he is a free poet and that his instincts suffice…”

– Le Corbusier, Towards A New Architecture, p. 74, on architects educated in the schools

Though his regulating lines positively functioned to govern what appears (see previous “The Governance of the Question” post, HERE), he was also working in a negating space of ideological tension with his enemies. So he made a hero out of the engineer and lifted up as exemplary the aesthetic of the grain elevator. Speaking of which…

Here is Le Corbusier critiquing the elitism and uselessness of the architectural schools of his day:

“There exists in France a great national school of architecture, and there are, in every country, architectural schools of various kinds, to mystify young minds and teach them dissimulation and the obsequiousness of the toady. National schools!

– Towards A New Architecture, pp. 14-15

Our engineers are healthy and virile, active and useful, balanced and happy in their work. Our architects are disillusioned and unemployed, boatful or peevish. This is because there will soon be nothing more for them to do. We no longer have the money to erect historical souvenirs…”

“Architecture is stifled by custom. The ‘styles’ are a lie.”

– Towards A New Architecture, p. 3

“The architects of to-day, lost in the sterile backwaters of their plans, their foliage, their pilasters and their lead roofs, have never acquired the conception of primary masses. They were never taught that at the Schools.”

– Towards A New Architecture, p. 31

So, Corbusier, in tense reaction against what he hated, was self-taught. There was some historical precedent to the aesthetic in which he was interested. Adolf Loos lived about an intellectual generation prior to Corbusier.

Speaking of ideological tension with the enemy on the polar opposite side of society, Adolf Loos is famous for his essay ground-breaking entitled “Ornament is Crime.” With that title in mind, compare Loos’ building in the photo above to the pre-existing edifice right next to it.

Here is Le Corbusier critiquing how the sense of the unity of the plan of the city had been lost to chaos and disorder in the previous 100 years because of capitalist developers. And, speaking of the crime of useless ornament:

“We have not forgotten the dweller in the house and the crowd in the town. We are well aware that a great part of the present evil state of architecture is due to the CLIENT, to the man who gives the order, who makes his choice and alters it and who prays. For him we have written ‘EYES WHICH DO NOT SEE.’

– Towards A New Architecture, p. 18-19

We are all acquainted with too many big business men, bankers and merchants, who tell us: ‘Ah, but I a merely a man of affairs, I live entirely outside the art world, I am a Philistine.’ [Do note Corbusier’s sarcasm] We protest and tell them: ‘All your energies are directed towards this magnificent end which is the forging of the tools of an epoch, and which is creating throughout the whole world this accumulation of very beautiful things in which economic law reigns supreme, and mathematical exactness is joined to daring imagination. That is what you do; that, to be exact, is Beauty.

Once can see these same business men, bankers and merchants, away from their business in their own homes, where everything seems to contradict their real existence – rooms too small, a conglomeration of useless and disparate objects, and a sickening spirit reigning over so many shams – Aubusson, Salon d’Automne, styles of all sorts and absurd bric-a-brac.”

So, Corbusier pushed for a town planning movement throughout Europe. Speaking of town planning, here is Le Corbusier critiquing the crowded and dirty cities:

“It is time that we should repudiate the existing lay-out of our towns, in which the congestion of buildings grows greater, interlaced by narrow streets full of noise, petrol fumes and dust; and where on each storey the windows open wide on to this foul confusion. The great towns have become too dense for the security of their inhabitant and yet not sufficiently dense to meet the new needs of ‘modern business.’”

– Le Corbusier, Towards A New Architecture, p. 54-57

Le Corbusier responded by proposing a City of Towers (see his Radiant City proposal, discussed in “Moving Around The Question,” HERE).

So, we have seen Corbusier tell stories of what it means to be a modern person. This means he has articulated the conditions of humans appearing and living in a modern world that is appearing to them. “Stories within stories” told of what this means include those of the “ground” of optical perspective, living on a globe rather than the earth, the death of the body and sensuality, governance by Idealism and progress, and individual movements according to the laws of mechanical motion. We have now also seen him both telling us and living a story of modern buildings and society being structurally held together in tension. Neither the conservative nor liberal, right nor left, escapes any of these stories that shape the conditions of our environment. Later, I will address how and whether Corbusier responded to these conditions as a fascist, and, perhaps, to what degree. For now, I need to tell another “story within a story” in order to get a better picture of what was being responded to in the first place.

Pingback: WAS LE CORBUSIER A FASCIST? The Land Where The Question Is Heard | Knowing God

Pingback: WAS LE CORBUSIER A FASCIST? The Mystery of the Question | Knowing God

Pingback: WAS LE CORBUSIER A FASCIST? Well, Yes, But… | Knowing God

Pingback: WAS LE CORBUSIER A FASCIST? A Question of Assertion or Play? | Knowing God

Pingback: WAS LE CORBUSIER A FASCIST? Our Current Common Conditions | Knowing God

Pingback: WAS LE CORBUSIER A FASCIST? Conclusion and Index | Knowing God