In my previous posts of this series – links HERE, HERE, HERE, HERE, HERE, HERE, HERE, and HERE – I was telling a story. It is a story about stories, in that it was prompted by three French journalists telling us a story – namely, that the famous 20th century architect Le Corbusier was a Fascist. It is a personal story, in that I am repulsed by fascism but love Le Corbusier. It is a geo-political story, in that Corbusier was born and raised, quite actually, right in the middle space between French cosmopolitanism and German Nationalism. It is also, of course, a story, about Le Corbusier and his work. To tell that story was to tell multiple “stories within a story,” which hopefully began to give a sense of why this blog series carries its title.

I then more directly addressed the question of whether, as the “secular liberal” journalists have claimed, Le Corbusier was indeed a Fascist (see “Well, Yes, But…” – HERE). We are confronted by an uncomfortable uncertainty. And, in response, we see that Le Corbusier and his work, like most anything else in the hands of either side of the political aisle, are, when placed in their grasp, turned into territory to compete over for power and control. What if part of the point of Le Corbusier’s work is to point us toward that fact? One of his works is called the “Monument To The Open Hand” – link HERE to see – in honor of humanity’s posture of receiving and giving with thanks.

Again, what I am doing here is telling a story. Every story has a setting. Both sides of the political aisle live inside a common environment with a common set of conditions – as explored as a summary of Le Corbusier’s work in my previous post, “Questioning As Play” (HERE). Architecture is a unique means of exploring this fact, because its history and present tell our collective story. Not just Corbusier but Architecture itself, by its very nature, does not speak the language of political rhetoric. Both sides of the political aisle inhabit and craft the space of our common architectural heritage. And, in this way, architecture is, at a visceral level, a kind of analogy to the larger environment that we all inhabit. And, we shape our environment. It, in turn, shapes us.

Le Corbusier’s work illuminates these facts in a particular way. In what way does his work do this? We could say that his work presents our common environmental conditions in the particular ways that we have discussed in the “stories within the story” explored in previous posts. We all live in an environment that shapes us to live inside a play among the very things revealed and articulated in Le Corbusier’s work. Without pretending that Corbusier’s work is comprehensive or of final authority, it remains true that we are all responding to our common environmental conditions put in play by him in various ways that said environment presents to us as options in the first place.

Now, hopefully, my reader is beginning to get a more full sense of why my blog series carries the title it does.

CORBUSIER’S WORK AS A KEY TO INTERPRETING OUR CONTEMPORARY POLITICAL ENVIRONMENT

Where ancients tended more so to build up from the local and contingent conditions given by the earth, modern persons and lives stand or fall upon a framed construct built into our history. The geometric rules of optical perspective developed in the Renaissance name this construct as the “ground” (as discussed in “The Ground of The Question” – HERE). Both left and right now have different versions of wanting to “burn it all down to the ground,” – whether the Patriarchy or Washington D.C. – apparently without realizing that they are constructing the ground in the first place.

Where ancients’ sense of identity and home was bound to the embodied limits of their horizon under the dome of heaven, moderns came to rely on the work of the mind to imagine themselves living on a globe in outer space, as discussed in “Moving Around The Question” – HERE. Contemporary political tensions are now, at least in part, governed by what feels to conservatives like predominant and inevitable global cosmopolitanism, in tension with a compulsive drawing of some semblance of more localized boundaries (even if said boundaries are drawn at a national scale).

We tend to imagine that the 1/6 QAnon shaman praying “against the globalists” in the US Senate chamber was just motivated by ideological discourse, but I submit that Architecture and its history helps us see how this has to do with the question of where our place or home is. We are all on a Homeric Odyssey of sorts. But, now that we live on a globe in the universe rather than on the earth inside the horizon, even our religion is cosmopolitan.

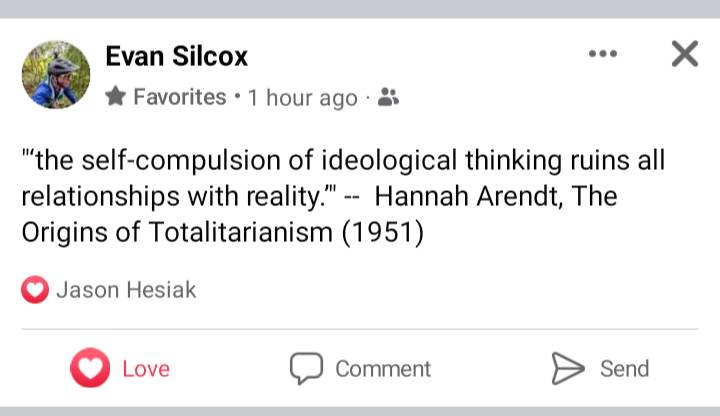

Ideological discourse asks us to pit totalitarianism against pluralism. Since this is a blog series exploring the question of Le Corbusier’s Fascism, however, I think it’s also important to mention another way that the spatial and technological relationships native to the practicing and inhabiting of architectural edifices helps us understand that politics is about more than ideological assertions.

Once living on the globe in a universe rather than on the earth inside the horizon, we all – whether of more pluralist or authoritarian bent – have totalizing tendencies.

As explored in “On the Body of The Question” – HERE – this different (from the ancients) orientation and understanding of home, place, and identity – regardless of our ideological commitment to left or right, conservative or liberal movements – means a new relationship with the body and sensuality. So, we are now tempted in new and perhaps unexpected ways to either divorce from or immersion with our bodies.

Contemporary conservative theology and law is committed to a disembodied “originalism.” Anti-government, or anti-“regulation” ideology is governed, at least in part, by dissociation from the body. By comparison, others tend to view truth as only and exclusively embodied. Similarly, the contemporary liberal proclaims sexual freedom, while the conservative dictates abstracted rules from above.

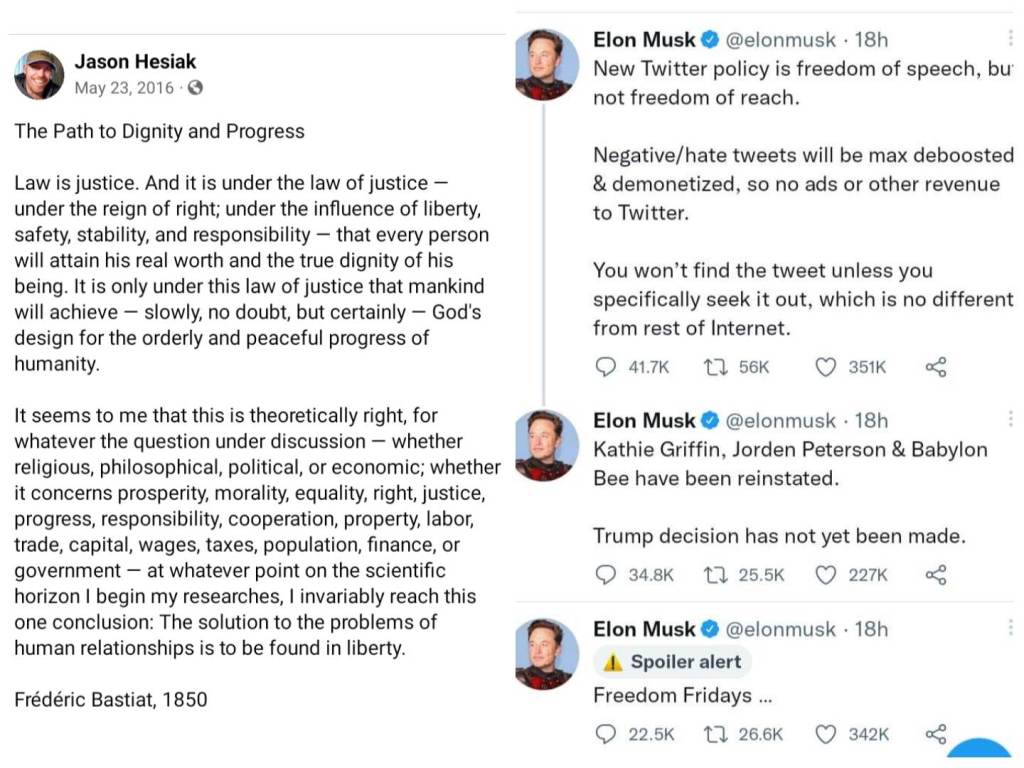

Where ancients valorized the heroic deeds of their ancestors and idealized heroes, and played their role to honor them in their own lives, moderns embarked on a larger-scale project of movement away from previous authorities. Instead, we moved towards optimistic progress governed by an Ideal image of both humanity and society. I talked about this in “On Governance of The Question” – HERE. This project wasn’t at the scale of our own lives or local community but of all of society, or even the entire globe. Where contemporary liberals proclaim “peace and free love” and are policed by the cynical, contemporary conservatives assert an ideal of free economic growth and resent the reality of sensed, embodied limits. This particular example of reciprocal relationships around governance and policing thus also functions as a form taken by our sense of truth being disembodied.

Corbusier’s prophetic image of the dead, hovering body rings true. None of our contemporary political activity is about crafting well ordered, proportional relationships in concrete reality. Idealism and cynicism are reciprocating twins, because they are both born of an abstracted “progress.” So, the way architecture gives us a spatial and symbolic sense of progress transcending the sensed horizon also helps us to better see that and how “progress” isn’t just a question of political rhetoric of left vs right, conservative vs liberal. This is also revealed in the fact that Frédéric Bastiat happens to be a hero to anti-progressive conservatives, whereas Elon Musk is hardly a “progressive.” And yet, they are both obviously “governed” by an image of social “progress.”

Progressive and anti-progressive turns out to be a reciprocal relationship that is geometrically similar to that of idealism and cynicism. It is also, in the same way, partly governed by our relationship with the spatial and technological environment.

To that end of optimistic progress governed by an Ideal image of both humanity and society, where ancients took advantage of machines to hoist the heavy loads of particular buildings, modern persons instead came to presume to function as machines to lift the heavy load of all of society. We got an image of this in “The Mechanics of The Question” (HERE). Whether as consumers or producers, or as managers, in business, marketing, or the music industry, we now tend to imagine society itself as a machine that aims towards predictably controlled outcomes. And, we also see political involvement as having individual “control” over our lives and world. Control, notably, is a mechanical term. Of course, too, we have parties adapting to common conditions in opposed ways competing for said control.

Ancients: “To do what would otherwise take much of the entire community, we lift heavy loads with a few people using machines that merely approximate the motion of the heavenly divinities, which determine the temporal cycles of the lives of said entire community.” Us now that we use our individual minds to imagine what was once heaven, but is now a disenchanted outer space, as our home: “I create my individual, personal reality using the Instagram machine.”

Or, being shaped by the machine, we rage reactionarily against it. What if the accusation of “virtue signaling” is partly just cynical distrust that no one not immersed in the social machine is not “creating their own reality”? So, we now also have an inescapably and reciprocally tied socio-political relationship between individualism and “group think.”

In that post on Corbusier and machines, we also explored the ancients took the circle and right angle to be the elements of mechanical motion. We now find ourselves standing in long, mechanically straight lines to wait and turn into the DMV. Where the ancients merely sought to use machines to free much of the community from the lifting of specific heavy loads, all of us now, whether committed or biased more to left or right, conservative or liberal parties, once we presume to function as machines, find ourselves bearing loads in common with one another. In the bureaucratic machine, the community is the heavy load. It’s well documented, for example, that “reality creation” on the Instagram machine correlates with increased depression and isolation. Though elements of the machine shape all of us, some of us just choose to respond to it differently from others. Of course, those different choices, such as “individualism” vs. systematic “group think,” or fantasy vs. reality, tend to be viewed as opposing one another.

The contemporary left uses the “straight lines” of abstract rules to run an administrative bureaucracy, not as embodied persons but as representational office holders inside “the system.”

Meanwhile, conservatives gravitate towards particular personalities able to exert authority, precisely, in part, because they subvert the bureaucratic administrative apparatus of the machine. Liberals tend to view this as “unpresidential” or “unprofessional.” Our disoriented relationship with embodied sense rings true again.

Where ancients lived inside the horizon and worked to make something appear, buildings and local communities held together like a woven fabric that appears over time (as in masonry). Where moderns live on the globe and thus by default have a total vision of everything from the mind’s eye at once, and set out on a project of movement away from ancient authorities, the elements of modern buildings and society come to be held together in tension – whether in open conflict or not. The re-bar, bolted joints, and beams in tension of modern buildings, serve as analogies to how the community of people who build them is itself held together. Le Corbusier helps us wrap our mind around this in “On The Structure of The Question” – HERE.

The inescapably bound and reciprocal socio-political relationships being described in this post turn out to generally be ones characterized by tension, a motion of pulling away from one another at opposing poles. In many of these ways, as well as others, we see contemporary liberals and conservatives competing for rule over the same territory – which, essentially, extends across the entire globe – while, at the same time, being defined and identified by their tensions pulling against one another. Humans are not able to hold the whole world in their hands. And, when they try, it instead tends towards pulling apart.

Here, we see a conservative Russian state TV host spontaneously using “Western” dance moves from the pop culture film “Pulp Fiction.” Further, as can be seen in the full video – HERE – he is doing so in identifiction with Ukrainian President Zelensky. Solovyov’s identity was here partly defined by the enemy with whom he is tied together in a state of tension.

Of course, to accuse others of “virtue signaling” is also partly to be structurally defined by one’s enemy, as well as by a dominating cynicism, itself tied in tension to modernism’s Utopian Idealism. I also, just this past week, saw a woman walking into the grocery store wearing a “Let’s Go Brandon” sweatshirt. If her sweatshirt wasn’t an identity marker, then the structural tension with the other pole, by which it appears, would not be relevant here. The contemporary left, too, appears to be “pulling in tension” against the very real and destructive practices of what they perceive as “the Patriarchy” or racialization. The two – left and right, sweatshirt-wearer and Applebee’s protester – identify and are defined by structural tension with one another, by which they are held together.

When our sense of home and identity is not oriented around what appears like a materially woven fabric over time but, instead, is about speculative work in the vacuous space of the mind, then the embodied presence who steps in for the previous “fabric” is an object we perceive as exterior and “other” to ourselves as our polar opposite.

German Theologian Karl Barth makes this identifying tension most explicit.

In my next post, I will finish “telling a story” of how Le Corbusier’s work can, in the face of our ideological assertions, function as a kind of key to interpreting the conditions of the environment in which we find ourselves before we ever make our way down a path of activism’s political proclamations. I will also conclude my blog series that thus asks, “Is Le Corbusier A Fascist?”

Pingback: WAS LE CORBUSIER A FASCIST? Conclusion and Index | Knowing God