In my previous posts – links HERE, HERE, and HERE – I was telling a story. It is a story about stories, in that it was prompted by three French journalists telling us a story – namely, that the famous 20th century architect Le Corbusier was a Fascist. It is a personal story, in that I am repulsed by fascism but love Le Corbusier. It is a geo-political story, in that Corbusier was born and raised, quite actually, right in the middle space between French cosmopolitanism and German Nationalism. It is also, of course, a story, about Le Corbusier and his work. And, it is a story with multiple other stories folded up inside a story. I have told a few of those stories inside a story, which hopefully began to give a sense of why this blog series carries its title. Now I want to continue to tell more of those.

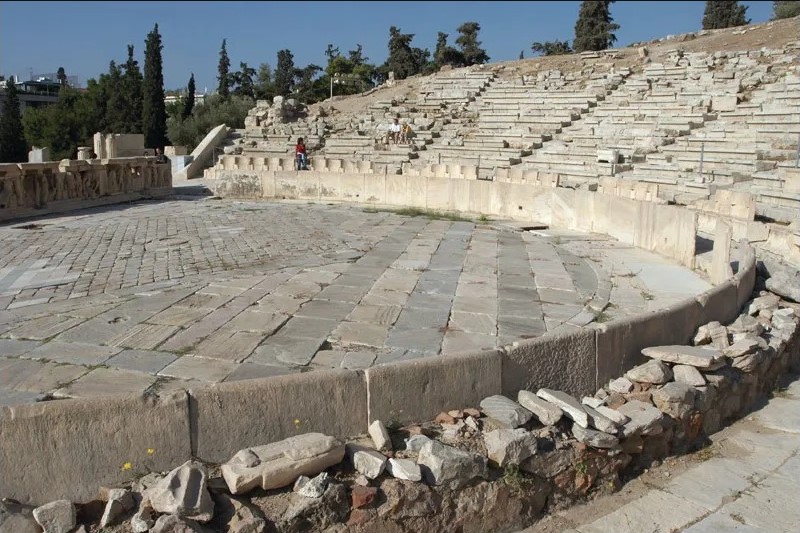

What appears before you here is the Classical Greek Theatre of Dionysus, which is situated on the Southern slope of the Acropolis. I chose this particular photo to give a sense of how what’s happening is about appearing before and between performer and audience. “Per” in its Latin roots means through, for, or against. It’s also about movement towards full completion or accomplishment. So, performance is about movement towards taking form fully. Of course, here, the contours of the theater itself are circular, because it is a microcosm of the earth. The axis along which appearing primarily occurs is vertical, between heaven and earth. It’s in ruins, because appearing doesn’t matter anymore (see previous two blog posts of this series, HERE and HERE).

What appears before you here is a photo of an Advent worship service at Salisbury Cathedral. In monotheism, theater becomes a line. Our appearing is situated along a trajectory between one ultimate Alpha and Omega.

Here, the horizontal axis is clearly analogical, because it occurs between two rose windows that image the beginning and end of ineffable eternity. Abbey du Thoronet is a precursor to those like Salisbury Cathedral, with the infamous Rose Windows, in that it similarly has circular openings to the light at both ends of the main chapel.

Hagia Sophia was the first Christian Cathedral of our history. Such spaces, in other circumstances besides an Advent service, were often lit by lanterns hanging along the margins of the space or, as in the case of Hagia Sophia, down from the ceiling.

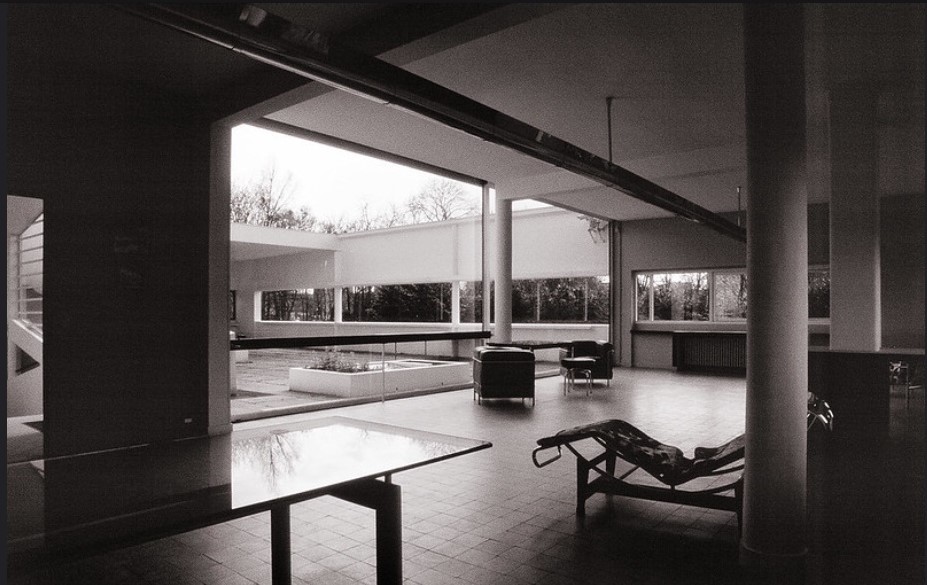

Here, historically after what appears is either divorced from physical reality or confined to the immanence of “this world,” the axis is not analogical. Rather, for Le Corbusier, the axis is an image of scientific, technological, and economic progress that governs what appears in the world. Now the axis along which appearing occurs is primarily horizontal rather than vertical.

“Religions have established themselves on dogmas, the dogmas do not change; but civilizations change and religions tumble to dust. Houses have not changed. But the cult of the house has remained the same for centuries. The house will also fall to dust…Our external world has been enormously transformed in its outward appearance and the use made of it, by reason of the machine. We have gained a new perspective and a new social life, but we have not yet adapted the house thereto.”

– Le Corbusier, Towards A New Architecture, p. 14-17

Such an axis is not a one off for Corbusier. One other example can be seen in his monastery at La Tourette, HERE. So, why do I say an image of progress “governs” what appears in the world? The image of progress is guiding Corbusier’s work, and Corbusier is working to articulate what it means to live in a modern world. Further, The reason I have to ask that question is because we don’t think of regulation or governance this way. When our image of time is no longer in reference to higher beings, we assume that and function as though the human person takes on the role of what was previously divine authority.

So, now we have begun to get a sense of how Le Corbusier was situating his work inside the history and tradition of Western architecture. But, he was up to something else. Or, a number of other things…

“Arrangement is the gradation of aims, the classification of intentions.”

– Le Corbusier, Towards A New Architecture, p. 5

Part of what the regulating function of the appearing of the axis accomplishes is also to help progress succeed.

“The machinery of Society, profoundly out of gear, oscillates between an amelioration, of historical importance, and a catastrophe…It is a question of building which is at the root of the social unrest of today: architecture or revolution.”

– Le Corbusier, Towards A New Architecture, p. 8

And, what appears here, for Le Corbusier, is fairly explicitly about progress. As a leader of the European atant-garde movement of the early 20th century, Corbusier was partly guided, or we could say “governed,” by progressive optimism.

“Primitive man has brought his chariot to a stop, he decides that here shall be his native soil…The pegs of his tent describe a square, a hexagon, or an octagon. The palisade forms a rectangle whose four angles are equal. The door of his hut is on the axis of the enclosure – and the door of the enclosure faces exactly the door of the hut…But in deciding the form of the enclosure, the form of the hut, the situation of the altar and its accessories, he has by instinct recourse to right angles – axes, the square, the circle. For he could not create anything otherwise which would give him a feeling that he was creating. For all these things – axes, circles, right angles – are geometrical truths and give results that our eye can measure and recognize, whereas there would be only chance, irregularity, and capriciousness. Geometry is the language of man.” –

Towards A New Architecture, by Le Corbusier, pp. 69-72

What appears before us here is the realization that, while telling a story the history of our loss of horizon and body, and while even asserting a story of progress, Corbusier never left behind the importance of what appears in ancient Greek theater. After all, we all do appear and disappear in the world and before each other.

“Our eyes are constructed to enable us to see forms in light.”

– Le Corbusier, Towards A New Architecture, p. 2

Keep in mind that we are talking about the governance of what appears. “Is Le Corbusier a Fascist?” is, after all, a political question. So far, we see that what governs what appears is the fact of appearing itself, the ordering of what appears, and social progress. In addition, we also see that Corbusier was interested in a purity and idealism. This is something we might collectively refer to as abstraction. They were, for him, all tied together, both to each other and to the other governing aims – formal causes – of his work.

“Architectural abstraction has this about it which is magnificently peculiar to itself, that while it is rooted in hard fact, it spiritualizes it. The naked fact is a medium for an idea only by reason of the ‘order’ that is applied to it.”

Le Corbusier, – Towards A New Architecture, p. 47

In the photos of Corbusier’s work displayed so far in this blog series, we can begin to get an intuitive sense of what he meant by “abstraction,” or “the naked fact.” But, what, exactly, is being abstracted? Well, to begin to answer that question, we have to ask what appears in architecture. And, if Corbusier is interested in theater, we also have to ask about per-formance. What appears in architecture is form.

“Architecture is the masterly, correct, and magnificent play of masses brought together in light. Our eyes are made to see forms in light; light and shade reveal these forms; cubes, cones, spheres, cylinders, or pyramids are the great primary forms which light revels to advantage; the image of these is distinct within us and without ambiguity. It is for this reason that they are beautiful forms, the most beautiful forms…Egyptian, Greek or Roman architecture is an architecture of prisms, cubes and cylinders, pyramids or spheres: the Pyramids, the Temple of Luxor, the Parthenon, the Coliseum, Hadrian’s Villa. Gothic architecture is not, fundamentally, based on spheres, cones, and cylinders…It is for that reason that a cathedral is not very beautiful and that we search in it for compensations of a subjective kind outside plastic art…The cathedral is not a plastic work; it is a drama..”

– Le Corbusier, Towards A New Architecture, p. 29-30

So, what governs the appearing of Le Corbusier’s work is the appearing itself, an aim towards order, social progress, optimism, and “abstraction.” We can also add a particular form of “idealism” to that list.

In the above quote, he refers to “primary” forms. In the Renaissance, following in the footsteps of a Classical tradition, these forms were named “Ideal forms.” In Classical antiquity, these Forms had divine significance. So, we see here that Corbusier wasn’t presuming the authority of his own person but was, instead, looking to authorities beyond himself. The shape of the “primary form” at Villa Savoye, in plan view, is close to a perfect square. In fact, the column grid is organized in a perfect square. The measure between the grid and the walls that extend past them is determined by modules generated by the geometric construction of the golden section.

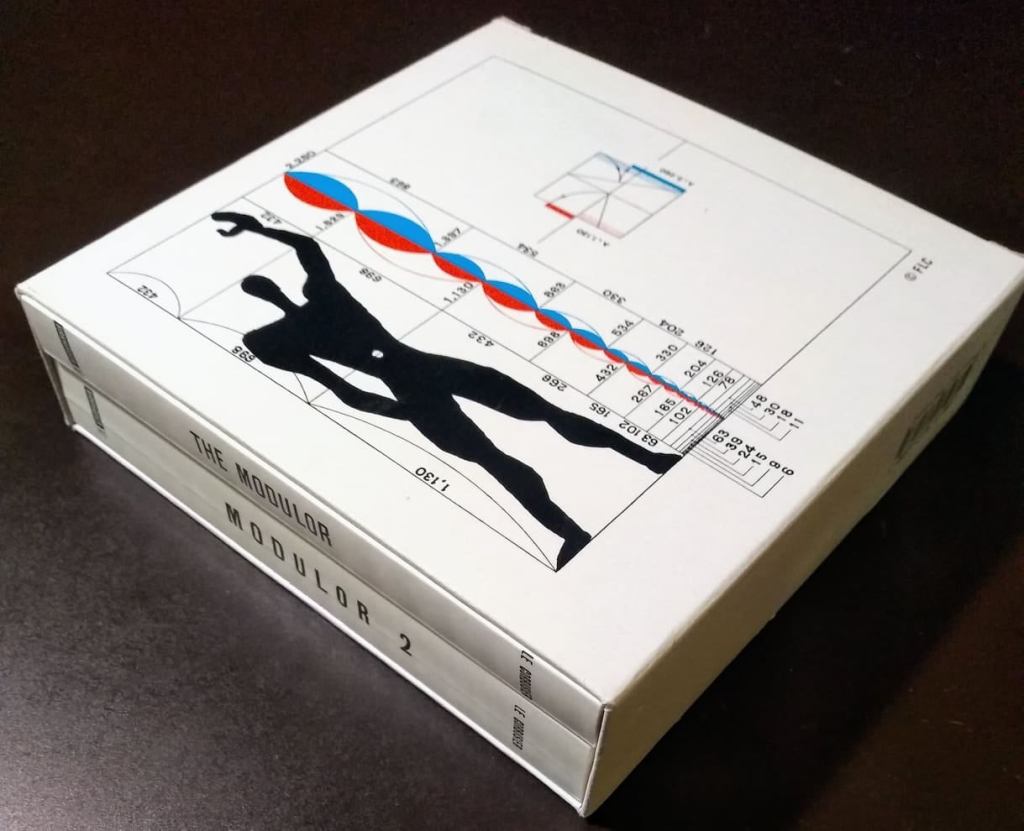

And speaking of the golden section, why did Corbusier say that we see architecture with eyes that are 5’-6” from the ground? All of us don’t, of course. It is a 6’ tall man whose eyes are 5’-6” from the ground. For Corbusier, this was the height of the ideal man. His Modulor was actually based on a 6’ tall British policeman!

What was the Modulor? It was a system of proportion he designed, used in his work, and advocated for standardized use in wider society. It is based on the fact of the golden number being found in and throughout not only nature but the human body. So, similar to Hercules for the ancient Greeks (see previous post, HERE), the 6’ tall British policeman was thought to be an Ideal image of humanity. This was not just because his proportions appear beautiful to us but also because the number that governs those proportions is found to “govern” what appears throughout nature.

Again, Corbusier is attempting to look to authorities beyond himself. Further, he sees the human body and nature themselves as naturally and inevitably “governed” by “higher authorities.” And, he is working to attune the buildings he designs to those “higher authorities.” The body of his work is “governed” or “regulated” by them.

“Architectural emotion exists when the work rings within us in tune with a universe whose laws we obey, recognize, and respect. When certain harmonies have been attained, the work captures us. Architecture is a matter of ‘harmonies,’ it is a ‘pure creation of the spirit.’”

– Le Corbusier, Towards A New Architecture, p. 19

Do note Corbusier’s indebtedness to Neoplatonism here. For more on the golden ratio and its appearance throughout nature, click HERE. The plan of Corbusier’s famous monastery at La Tourette is also “governed” by the golden rectangle.

So, we have seen Corbusier tell stories of what it means to be a modern person. This means he has articulated the conditions of humans appearing and living in a modern world that is appearing to them. “Stories within stories” told of what this means include those of the “ground” of optical perspective, living on a globe rather than the earth, the death of the body, and sensuality. And, now we have also seen that what “governs” the story Corbusier is telling with his work is a version history and progress, of optimism and Classical Idealism.

We have seen in this post that the question of governance or regulation is, at least partly, tied to our relationship with both divinity and the body. When our image of time is no longer in reference to higher beings, and where our image of identity or reality is unconstrained by the contours of the horizon or the body, either the body wants to set its own rules, or the person takes on the role of divine authority. Corbusier’s response to that is to present a different image of the relationship between the body and higher authorities from that one.

I want to draw out a few points here. First, I am telling a story about the common conditions in which we all live, about the simple “fact of the matter.” Yes, Corbusier is partly here “asserting” or hoping for social progress and classical beauty. At the same time, however, this was not new. With both his avant-garde progressivism and his Idealism, he was picking up on threads of tradition present for at least hundreds of years before him. In that sense, he was both asserting what he wanted and, at the same time, describing elements of modern conditions.

Second, for Corbusier, the optimism of social progress was tied into his more ancient Classical Idealism. They were neither separate nor contradictory for him, as our predominant tensions between conservative and progressive might suggest. They are tied together here, because Corbusier’s image of social progress is an ideal vision of society, itself based on an ideal image of humanity. I will address this later when I more directly address the question of Corbusier’s Fascism.

Third, though it was partly subjective – and I will get to that, too, later, when I more fully address the question of his actual ties to fascism – his Idealism was partly “objective.” Here’s Le Corbusier on his meeting with Albert Einstein:

“That same evening Einstein kindly wrote to me of the ‘Modulor,’ ‘It’s a set of proportions that makes the bad difficult and the good easy,’…”Some see this assessment as lacking in scientific rigor. Personally I find it extraordinarily clear-sighted. It’s a gesture of friendship from a great scientist to those of us who are in no way scientists, but rather soldiers on the battlefield.”

– Le Corbusier

In my next post, I will continue to tell stories folded inside the story of how Le Corbusier and his work both articulate the conditions of modern life and constitute a response to it. I will then more directly address the question of whether Corbusier was a Fascist.

Pingback: WAS LE CORBUSIER A FASCIST? The Mechanics of the Question | Knowing God

Pingback: WAS LE CORBUSIER A FASCIST? The Structure of the Question | Knowing God

Pingback: WAS LE CORBUSIER A FASCIST? The Land Where The Question Is Heard | Knowing God

Pingback: WAS LE CORBUSIER A FASCIST? The Mystery of the Question | Knowing God

Pingback: WAS LE CORBUSIER A FASCIST? Well, Yes, But… | Knowing God

Pingback: WAS LE CORBUSIER A FASCIST? A Question of Assertion or Play? | Knowing God

Pingback: WAS LE CORBUSIER A FASCIST? Our Current Common Conditions | Knowing God

Pingback: WAS LE CORBUSIER A FASCIST? Conclusion and Index | Knowing God