In my previous posts of this series, I was telling a story. It is a story about stories, in that it was prompted by three French journalists telling us a story – namely, that the famous 20th century architect Le Corbusier was a Fascist. It is a personal story, in that I am repulsed by fascism but love Le Corbusier. It is a geo-political story, in that Corbusier was born and raised, quite actually, right in the middle space between French cosmopolitanism and German Nationalism. It is also, of course, a story, about Le Corbusier and his work. To tell that story was to tell multiple “stories within a story,” which hopefully began to give a sense of why this blog series carries its title.

I then more directly addressed the question of whether, as the “secular liberal” journalists have claimed, Le Corbusier was indeed a Fascist. We are confronted by an uncomfortable uncertainty. And, in response, we see that Le Corbusier and his work, like most anything else in the hands of either side of the political aisle, are, when placed in their grasp, turned into territory to compete over for power and control. What if part of the point of Le Corbusier’s work is to point us toward that fact?

So, in my previous post, I articulated that competed-over territory as an analogy to our common environment – which, for us all and before we ever make any political proclamations, whether committed ideologically to left or right – sets the conditions that form who we are and frame the possibilities for the paths before us. How does Le Corbusier’s work “tell a story” of those conditions? How do we continue to see that story playing out in our contemporary world?

To answer that question in conjunction with “stories” told in Le Corbusier’s architecture, we moved through “stories within a story” of our wanting to “burn it all down to the ground,” of tensions between globalism and horizonalism, of disembodiment and immanence, of progress and petrification, of idealism and cynicism, of mechanical controls, their burdens, and politics as control, of mechanical rules and authoritarian personality cults, and of structurally being defined by our also being “held together in tension.” So, to pick up where we left off:

When our modern projects “grounded” in a universal, Utopian vision centered in the cities held together in tension with one another appears to climax and fall to pieces through the course of World War II and its ending, Le Corbusier responds by letting “the ground” give way to “the land.” The world as it had been known had disappeared, gone up in flames. So, we needed something else to stand on. Some respond by wanting our society “grounded” in abstracted fantasies to give way to gestures toward something older, more concrete, local, and stable, such as “the land.” Meanwhile – as mentioned in “The Land Where The Question Is Heard” (HERE) – the contemporary American vote is largely determined by how closely oriented one’s way of life is to the land. Though the joke in the linked video HERE is that “working outside” is turned into an identity, why would that particular choice be made in the first place? Turns out we never stopped being made of dust and breath.

Our common spatial and technological conditions of the modern world also set up reciprocal relationships in how we practice knowing. Where ancient knowledge was produced by interpretation of what was given to appear to us, moderns come to doubt what’s given but presume certain knowledge by the workings of our minds. When such presumptions to what eventually came to be practiced as global human mastery climaxed and failed with WWII, Corbusier, along with many others, responds in such a way that optimism and progress give way to complexity and nuance, curiosity and mystery, to have transcendent clarity move to the background of embodied vitality. This was explored in “On The Mystery of The Question,” HERE.

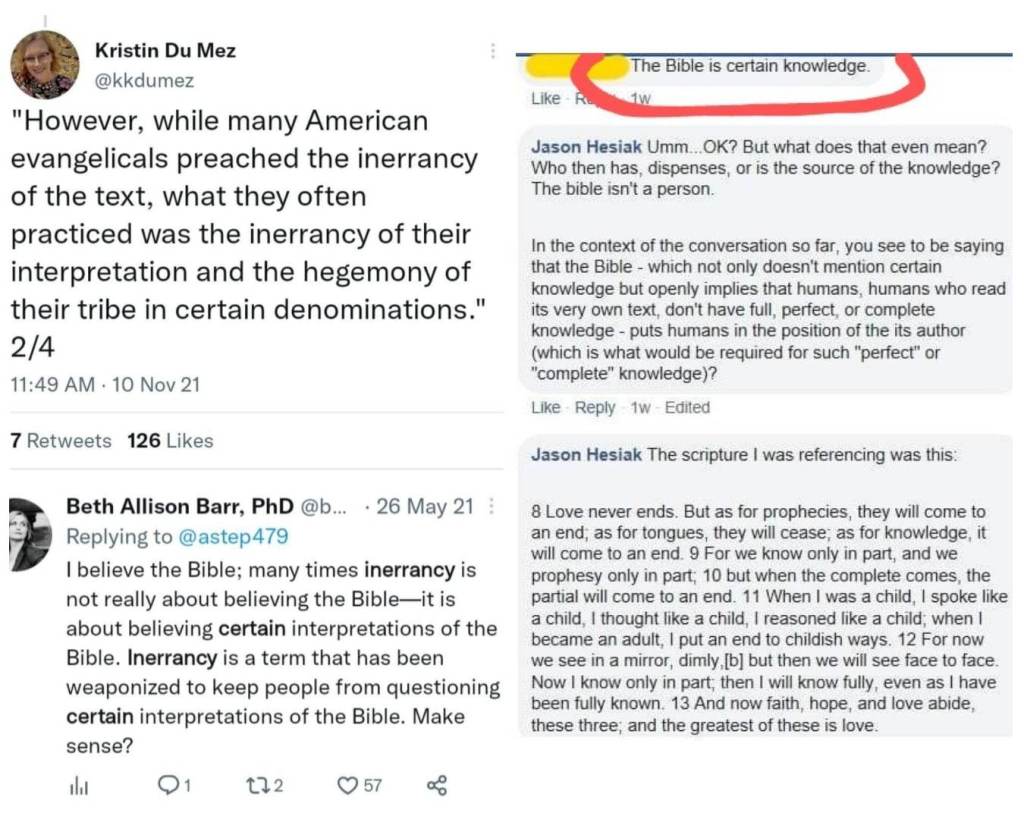

Now, we see the contemporary conservative grasping firmly to presumptions of certain knowledge, while the leftist reacts against that by using modern tools of rational critique to point out how certainty functions to scaffold abusive authoritarianism (which isn’t to say that they aren’t right in some way). Stories of disorientation to the body and identity formation around poles in tension with one another ring true again.

Our common spatial and technological conditions of the modern world even seem to have a role in shaping our orientation to “religion.” When ancients lived inside the horizon under the dome of heaven and practiced knowing according to what was given to their embodied senses, their communities tended to be organized around temple sites. These temples themselves functioned as vertical axes of union between heaven and earth, hidden and revealed. By contrast, when, with the speculations of the mind, we came to see our home as a globe in outer space, doubt ancient authorities, and embark on projects of mastery of the entire known universe, the primary axis around which our societies are oriented came to be the horizontal. Nothing is hidden anymore. And, as said societies turn secular, we tend to either reject or not be tuned in to ancient Temple imagery of a vertical axis uniting heaven and earth. This was referenced in “The Mystery of The Question” (and discussed in “The Governance of the Question”).

Throughout the series, then, we also implicitly saw multiple references to Corbusier’s playfulness with the sacred and profane, religious and secular, heaven and earth. These are also elements of our environment and history not only that we all encounter in the modern world but that shape us. As it turns out, there is still a sky above us, and a shared history we all inhabit. We still do, then, tend to be taken by a visceral sense of wonder at and submission to something greater than and above ourselves.

We imagine that we function according to a default atheism. But, do we, really?

CONCLUSION

We are each and all responding to our common environment in different ways.

Are we reconciling to or with it, or are we reacting against it? Are we adapting resiliently and thriving, or are we trapped inside a compulsive trauma response? How does our environment shape us to respond? What possible pathways do the conditions of our environment leave open to us?

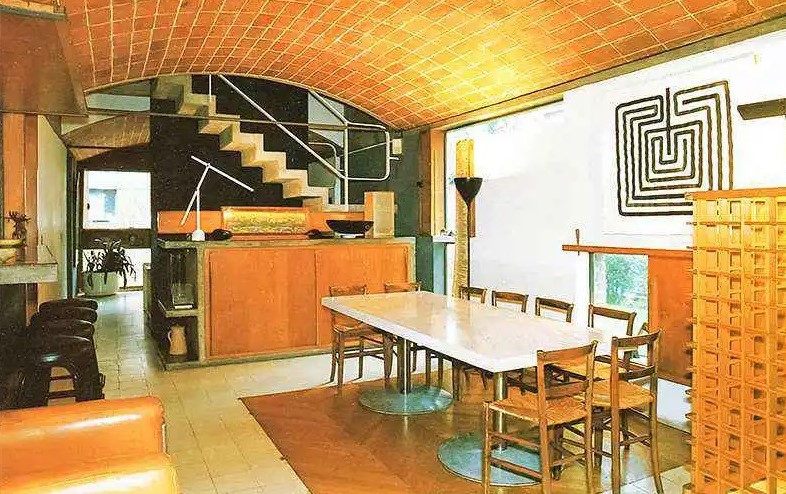

Perhaps reality is more complex and nuanced than ideological assertions tend to allow. To, in the face of easy answers, instead embrace the vulnerability of mystery and curiosity is to inhabit, and potentially better see, the difference between ideology and concrete reality. Corbusier seemed acutely aware of this. Do notice the Labyrinth at his Maison Jaoul.

To embrace mystery is also to see how the competitive critique of ideological discourse often misses the beauty and wonder of actuality, presence, and creation.

Again, was Corbusier making assertions, or was he reconciling to the reality of the conditions with which he was presented and that he observed. Was he critiquing, or was he articulating what it means for something to appear in the world? Or, was he actually making something appear in the world? Where was he articulating or critiquing, and where was he observing and reconciling? Even these questions don’t have simple, pat answers. And yes, his work is itself open to important critiques.

What implications does my questioning of Le Corbusier’s supposed Fascism, and of our ideological discourse more generally, have for our contemporary political engagement? How do we interpret our environment? One thing it doesn’t mean that both sides of the political aisle are the same, or that the setting of boundaries around deception and abuse is inappropriate or not called for. It does not mean that some responses to our environment are not more destructive than others. One thing it does mean is that we can’t reduce one side to racism and homophobia. There is more going on than that, and much of it is actually hidden, not inside but by our ideological discourse. It also means that we can’t identify totalitarian tendencies with one side only, or pigeonhole progress on progressives. What is going on is more complex than that. Our bodies, inhabiting the inside of spatial relationships, have a knowing. And our discourses have limits.

Giving attention to our visceral relationship with our shared spatial and technological environment rather than foreclosing potentials hidden by ideological discourse and jumping ahead to easy answers thus means and requires embracing our human limits and vulnerability. This line of questioning, and this leaning into curiosity and mystery of presence in concrete reality means better understanding of one another. It means compassion and curiosity, particularly and especially where we might otherwise exclude and tear down (which, yes, is different from boundary setting). Neither the conservative nor liberal, right nor left, escapes some relationship with any of the “stories within a story” that shape the conditions of our environment and formation of our person that Le Corbusier tells us about.

So, again I ask: was Le Corbusier a Fascist?

INDEX TO – WAS LE CORBUSIER A FASCIST?

The Ground of the Question – link HERE

Moving Around the Question – link HERE

The Body of the Question – link HERE

The Governance of the Question – link HERE

The Mechanics of the Question – link HERE

The Structure of the Question – link HERE

The Land Where The Question Is Heard – link HERE

The Mystery Of The Question – link HERE

WAS LE CORBUSIER A FASCIST? Well, Yes, But… – link HERE

WAS LE CORBUSIER A FASCIST? A Question of Assertion or Play? – link HERE

Our Current Common Conditions – link HERE