In my last post – link HERE – I began to tell a story. It is a story about stories, in that it was prompted by three French journalists telling us a story – namely, that the famous 20th century architect Le Corbusier was a Fascist. It is a personal story, in that I am repulsed by fascism but love Le Corbusier. It is a geo-political story, in that Corbusier was born and raised, quite actually, right in the middle space between French cosmopolitanism and German Nationalism. It is also, of course, a story, about Le Corbusier and his work. And, it is a story with multiple other stories folded up inside a story. I told one of those stories inside the story at the end of my previous post, which hopefully began to give a sense of why this blog series carries its title. Now I want to tell more of those.

When you enter the Acropolis in Athens, you approach the front of the Parthenon. The basic idea is that Temple and human person are appearing standing and facing each other. Seen here is the face behind which the statue of Athena is housed. The Parthenon has another face, figuratively speaking, on the back side. As the religious procession moves along, the community and Temple face one another again, where what lies behind the Temple face this time, however, isn’t the figure of Athena but the city’s housing of gifts and offerings to their goddess. At both points in the procession, community and Temple appear facing one another.

Similarly, at Reims Cathedral, community and Cathedral appear facing one another. In fact, a Medieval cathedral typically has a Plaza in front of it to house said community.

By comparison, as an individual enters the site of Le Corbusier’s famous Villa Savoye, completed in 1929, they are first faced with a view of the rear.

And only then does one move around essentially the entirety of it before coming around to stand face to face at the front. Why do you imagine that might be?

Before beginning to answer that question, I want to tell another story within a story.

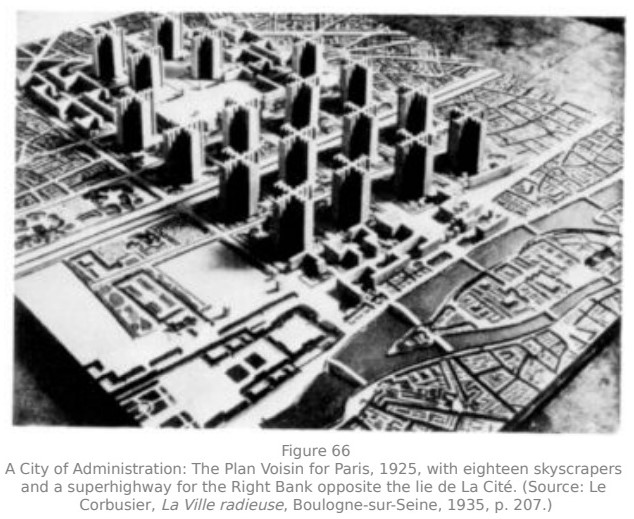

Seen here is a model of probably Le Corbusier’s most famous example of a city planning project. Much could be gleaned from this story, but the basic idea I want to take away from it for our purpose at the moment is that, similar to Villa Savoye, it was to have unity of aim and intention, thus appearing clean, orderly, and uniform. Except here, “it” was a vision for an entire city rather than one family’s Villa. It was also to be characterized by vast, relatively open spaces with grand views.

This is the Marais quarter of Paris. For what is the Marais quarter famous?

“The Marais is one of the most popular quartiers of Paris. And no wonder — it’s famous for old-world charm, narrow cobblestone streets, hidden courtyards & tranquil gardens, a multitude of mansions called hôtels particuliers, a vibrant Jewish community, and a thriving gallery & cafe culture.” – quote from HERE

In other words, it’s the polar opposite of Corbusier’s Radiant City. Where the Radiant City had “a unity of aim and intention,” grand views, and vast spaces, the Marais quarter is a picture of confinement to embodied human limits and smaller, more intimate spaces. It’s also what Corbusier wanted to raze to make room for his modern city planning vision.

So, where ancient buildings appeared standing face to face with the human community, we see Corbusier articulating a modern architecture in which the building only appears to the individual as we move around the whole with a circular motion. And, where Medieval Paris was characterized by smaller, intimate, embodied human spaces and what we would now look back and term “eclecticism,” Corbusier wanted unity, purity, and vast openness.

We are getting closer to seeing why Corbusier approaches Villa Savoye differently from how Phidias approaches the Parthenon. One more story within the story of Corbusier and his work will make it more clear.

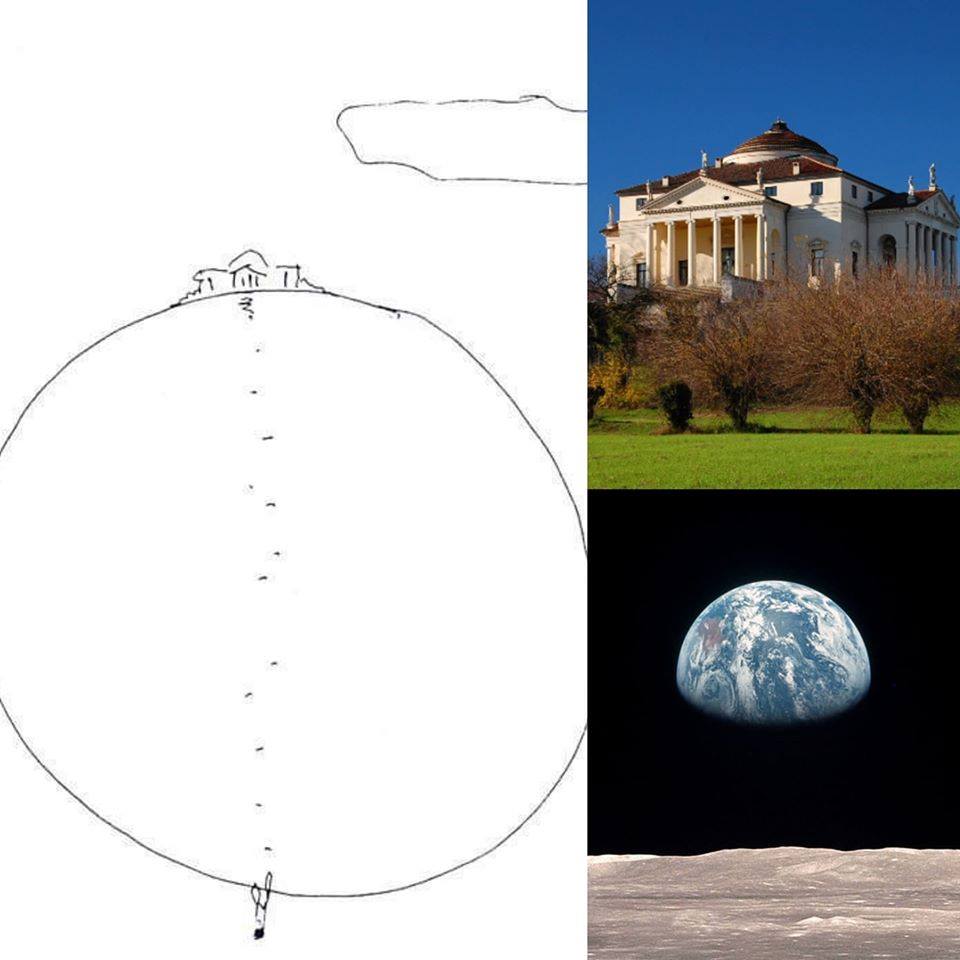

“At that time man had begun to lose his sense of mystery in relation to the horizon. The horizon was no longer the edge of man’s world, nor any longer the place where things appeared into his world. The earth had become a globe, so, upon visiting Palladio’s Villa and having a conversation with him, he instructed that I imagine someone setting off from one of the four faces of his Villa, walking all the way around the globe, and mysteriously coming back upon the very same face staring back at me.” – Sverre Fehn (architect), on Palladio’s Villa Rotunda

Above is Fehn’s sketch referenced in his conversation with Palladio, along with photos of the Villa and the at the time newly imagined globe, except from outside it. Palladio’s Villa Rotunda was finished in 1592. This was the intellectual generation of Galileo.

St. Peter’s Square is a Baroque Plaza designed by the famous sculptor and architect Bernini, completed in 1667. Obviously, it’s not a square. In fact, it’s in an oval shape and is meant to approximate the elliptical turning of the planets around the sun. This is how one moves around Le Corbusier’s Villa Savoye before coming to face the front.

Above is a collage of two photos of a tower designed by Le Corbusier and completed in 1960. See how the faces turn around each other, like at Villa Rotunda, and, perhaps, like a clock? Newton’s “Clockwork Universe” came along not too long after Bernini’s visions, which were themselves meant to be in harmony with Galileo’s cosmology. The faces of Villa Savoye are actually doing something similar to Villa Rotunda and St. Peter’s Square, but, as compared to this tower, it’s less obvious in photos.

How can we describe what’s happening here? Let’s back up and review. The Parthenon and Reims Cathedral appear face to face with the local community, feet planted upon the earth, our head standing up towards heaven. What appears does so by and through embodied human senses, defined by the horizon’s limits. This is our world; this is our dwelling. And, speaking of dwelling, both the Parthenon and Reims are dwelling places for the community’s divinities, vertical axes where heaven and earth meet.

Villa Rotunda and St. Peter’s Square, on the other hand, inhabit Baroque space. Baroque space appears with and from a point of view located not in embodied human sense but in the speculative logic of the mind. That’s why the faces of Villa Rotunda turn to multiple imagined positions in space simultaneously (the difference between the mind and body in this sense is made explicit in Aquinas’ Summa Theologica). And, this is why Corbusier’s Radiant City was to have “unity of aim and intention” with grand views of massive, open spaces. We might say that the place from which it is imagined is a view of the totality of everything. We thus might say that its aim was “totalizing.” Similarly, St. Peter’s Square inhabits an outer space, a point of view not only not defined by the limits of the horizon but definitively and positively referencing and pointing to what is beyond it.

Now do we have a better sense of why, at Villa Savoye, one actually approaches from the rear and moves around the whole in a circular motion before coming to stand face to face with the front? Does it seem like Le Corbusier is here more primarily asserting and prescribing or observing and reconciling to the conditions in which modern humanity dwells?

The question of whether Corbusier was actually a Fascist remains, but have we begun to get a better sense of why it’s an intriguing and important question? Where does the Fascist place him or herself? The cosmos, the globe? Where do the fascists dwell? From where does he or she perceive reality? The earth, the city, the universe? Are the potential answers to these questions any different for a leftist?

All of us inhabit the history of our art and architecture, whether we realize it or not, whether we commit to the left or to the right. We are all responding to the conditions of our common environment, in one way or the other. I will further address the question of response later. And, yes, some responses are more destructive than others. For now, I am trying to demonstrate how Corbusier was telling stories of the conditions in the first place, the environment in which modern humans find themselves. There are still a number of other stories within stories to tell to get a better and more full sense of these conditions.

Pingback: WAS LE CORBUSIER A FASCIST? The Body of the Question | Knowing God

Pingback: WAS LE CORBUSIER A FASCIST? The Governance of the Question | Knowing God

Pingback: WAS LE CORBUSIER A FASCIST? The Mechanics of the Question | Knowing God

Pingback: WAS LE CORBUSIER A FASCIST? The Structure of the Question | Knowing God

Pingback: WAS LE CORBUSIER A FASCIST? The Land Where The Question Is Heard | Knowing God

Pingback: WAS LE CORBUSIER A FASCIST? The Mystery of the Question | Knowing God

Pingback: WAS LE CORBUSIER A FASCIST? Well, Yes, But… | Knowing God

Pingback: WAS LE CORBUSIER A FASCIST? A Question of Assertion or Play? | Knowing God

Pingback: WAS LE CORBUSIER A FASCIST? Our Current Common Conditions | Knowing God

Pingback: WAS LE CORBUSIER A FASCIST? Conclusion and Index | Knowing God