In my previous posts – links HERE and HERE – I was telling a story. It is a story about stories, in that it was prompted by three French journalists telling us a story – namely, that the famous 20th century architect Le Corbusier was a Fascist. It is a personal story, in that I am repulsed by fascism but love Le Corbusier. It is a geo-political story, in that Corbusier was born and raised, quite actually, right in the middle space between French cosmopolitanism and German Nationalism. It is also, of course, a story, about Le Corbusier and his work. And, it is a story with multiple other stories folded up inside a story. I have told a couple of those stories inside a story, which hopefully began to give a sense of why this blog series carries its title. Now I want to continue to tell more of those.

When the Parthenon is a model piece of Architecture, the classical harp is a predominant musical instrument. Compare and contrast:

When Le Corbusier’s Villa Savoye is an iconic piece of Architecture, the classical piano is a predominant musical instrument. Or, perhaps, a violin. What do the harp and the Parthenon have in common, which differs from the piano, the violin, and Villa Savoye? Conversely, what do Villa Savoye, the classical piano, and the violin have in common, which contrasts with the Parthenon and harp?

Remember that, in our last story (link HERE), we told of how Baroque space appears with and from a point of view located not in embodied human sense but in the speculative logic of the mind. The faces of Villa Rotunda or Villa Savoye appear before a body imagined to be standing and facing the building in multiple positions at once. This is something the mind can accomplish but, obviously, the body cannot. Similarly, the imagined point of view of the space inhabited by St. Peter’s Square is outer space, a place the body does not and cannot dwell. By contrast, the Parthenon appears to a communal body standing face to face, front to front, with the edifice.

Is it any surprise then, that the Parthenon and the harp present an image of the human body standing upright upon the earth, like a classical Greek column? By comparison, does it not “make perfect sense,” then, that the piano is essentially the living body of a harp turned horizontal and floating in the air? And, is that not precisely what Villa Savoye is? In what position does a dead body lay when death has arrived? Is a body of thought laid upon or in the earth? Or is thought floating in the air?

Does my reader imagine that Le Corbusier is here asserting the death of the body and, conversely, the life of the mind? Or, is Corbusier playing the role of the poet, which is to reconcile with death?

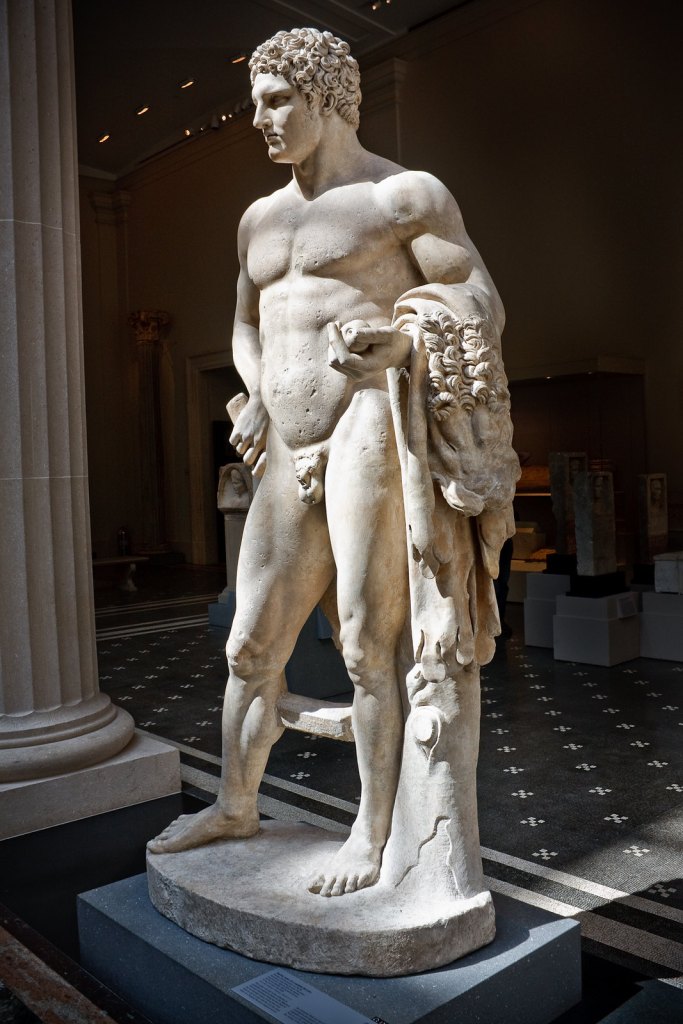

Seen here is an ideal human figure of classical antiquity, carved from a block of marble. More specifically, it’s a Roman statue of Hercules, dated 68-69 A.D. By comparison:

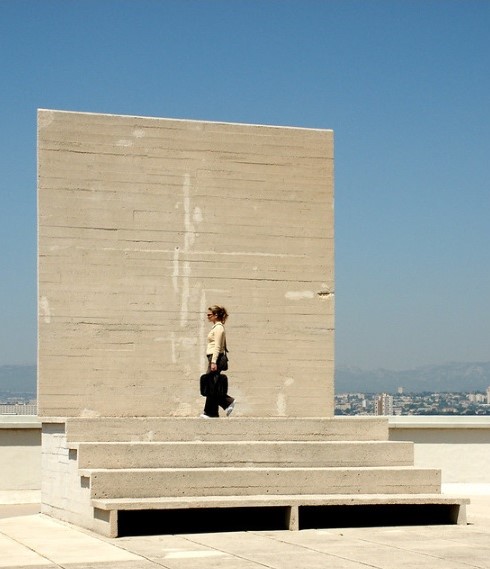

Seen here is Le Corbusier’s version of an ideal human figure of modernity. Specifically, it’s Corbusier’s Modulor Man type-cast into the poured-in-place concrete at his Unite d’Habitation in Marseille, France, design completed in 1945. The geometry of the ideal man was the basis of Corbusier’s system of harmonious proportion by which he organized all spatial relationships in his work.

Where the scholar of Roman antiquity crafted letters of his hand, the sculptor made Hercules appear by carving with said hands. See that the embodied figure that appears to us stands forth and fills out the space with its presence.

“The sculpture is already complete within the marble block, before I start at work. It is already there, I just have to chisel away the superfluous material.”

– Michelangelo Buonarroti.

Le Corbusier was doing the inverse of that. Where the scholar of modernity makes an impression upon the mind with mechanical, type-cast letters that serve as an analogy to the standardized and industrialized fabrication of modern buildings, Corbusier sculpts an image of the body whose ideal figure is essentially not present. Where the body appears to us here, it does so in its very absence, by the impression it leaves in the concrete that itself remains present to us. To “type” essentially means “to make an impression” (for reference, click HERE). Corbusier is telling a poetic story of the building’s being made.

For a less “poetic” and more “practical” telling of what Corbusier was doing in with his Modulor, “On the Dislocation of the Body in Architecture: Le Corbusier’s Modulor” – link HERE – is the best summary I have seen of it. If we continue to bear in mind the question of whether Corbusier is describing or prescribing, along with what I take to be the important realization that we have bodies and that they are a part of who we are, then a question thus arises of the place of embodied sensuality, emotion, and the elements of nature in life and architecture. If, as modern humans, we occupy a space that centers on and is oriented around the life of the mind and the figurative death or absence of the body, then do we leave our senses and the nature’s elements behind?

“Man looks at the creation of architecture with his eyes, which are 5 feet 6 inches from the ground. One can only deal with aims which the eye can appreciate, and intentions which take into account architectural elements. If there come into play intentions which do not speak the language of architecture, you arrive at the illusion of plans, you transgress the rules of the Plan through an error of conception, or through a leaning towards empty show.”

– Le Corbusier, Towards A New Architecture, p. 5

“The elements of architecture are light and shade, walls and space.” – Le Corbusier, Towards A New Architecture.

If our mechanical mode of standardized production makes abstracted planes of synthetic materials, then do we live in the forgetting of embodied depth and texture, contour and touch, light and shadow? What would that mean for human life if we did?

“The Architect, by his arrangement of forms, realizes an order which is a pure creation of his spirit; by forms and shapes he affects our senses to an acute degree and provokes plastic emotions; by the relationships which he creates he wakes profound echoes in us, he gives us the measure of an order which we feel to be in accordance with that of our world, he determines the various movements of our heart and of our understanding; it is then that we experience the sense of beauty.”

– Le Corbusier, Towards A New Architecture, p. 1

Other examples at Villa Savoye of “affecting our senses to an acute degree” can be explored HERE – that’s greenery from the roof garden in the window, by the way, which would be wondrous in summer), HERE, HERE, and HERE.

We might imagine or assume that the smooth, uniform, surfaces, and the mechanically and synthetically produced materials of Corbusier’s buildings aim to negate and leave behind the organic textures and presence of nature and the human body. One thing that’s most striking about visiting Villa Savoye in person, however, is precisely the opposite of that. In person, the uniform surfaces tend to be as much about what they play up against and reveal as the surfaces themselves – trees in the background, bathing of the sunlight, contours of human skin, all countered against the abstract nothingness of a “pure” white background.

I tried to point towards this same idea in my drawing upon visiting Le Corbusier’s Villa La Roche-Jeanneret:

So we find that Corbusier is actually engaged in a light playfulness with and against the weight of things rather than simply presenting an image of the person and reality that forgets the density of our connection to and origin with the earth. Where the floating horizontal body of the piano or Corbusier’s type-cast Modulor Man impresses the absence or death of the body upon us, the surfaces of his buildings themselves become a kind of absence in the background that is meant to make the organic skin and sound of the human body, the green of the plants, or the blue of the sky (ex. HERE) stand out in precisely the ways they might otherwise be forgotten in a space dominated by the silent and interior life of the mind.

And we see this same kind of intentional playfulness in his later work, with poured-in-place concrete rather than “purely” smooth, white surfaces. Other examples of this overall can be seen HERE, HERE, and HERE.

So, we have now seen Corbusier telling a few stories of what it means to be human person in the modern world. He tells stories of modern humans perceiving primarily with the eye on the “grounds” of an optical perspective. And, he tells stories of what it means to inhabit a space of the whole globe that is only understood from the speculative distance of the mind, which itself turns into a story or question of our relationship with the human body, sensuality, and the elements of the earth. We are, perhaps, now getting a better sense of how Corbusier helps us articulate the conditions of an environment we all inhabit.

We have briefly mentioned that he was raised up in the space between French cosmopolitanism and German Nationalism, but we are now beginning to see how he, in particular, has chosen to respond to our conditions in a more detailed, complex, and nuanced way than what such political categories might mean. The question of whether or not he was “really” a Fascist remains, as does how the story of Corbusier and his work helps us understand some contemporary responses to our common environment. For now, I want to continue telling more stories inside the story of Corbusier’s work, to help us continue to get a sense of the environment that surrounds us.

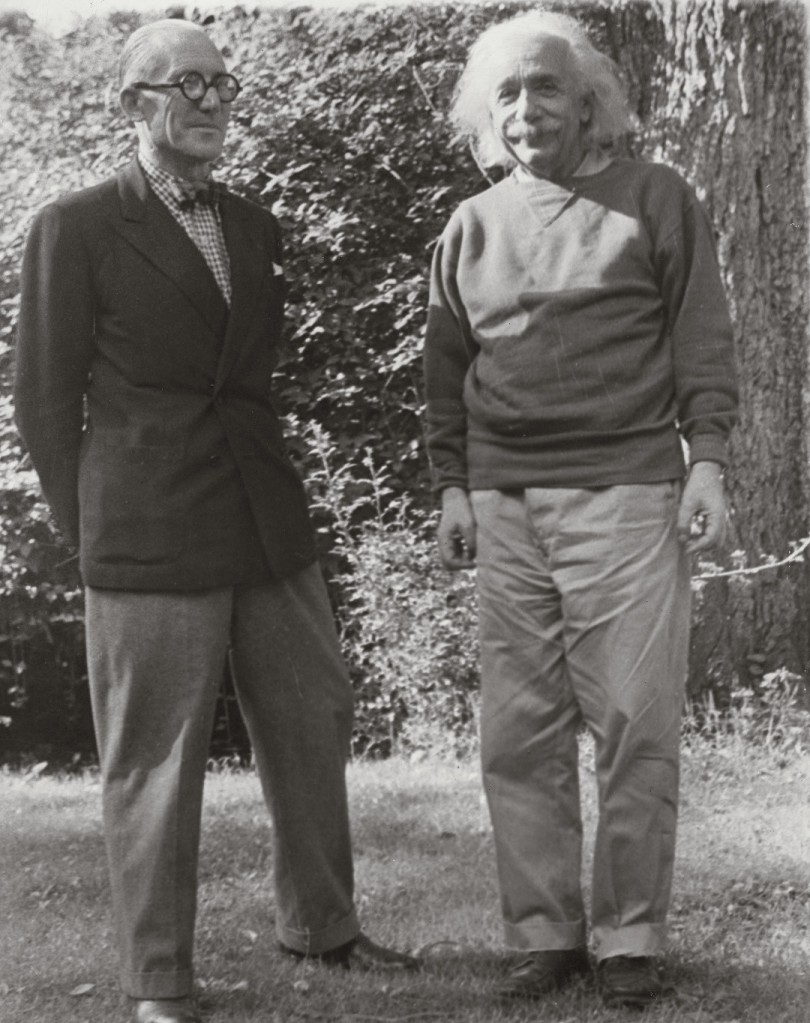

P.S. – Here’s Le Corbusier with Einstein, who, by the way, was Jewish.

Pingback: WAS LE CORBUSIER A FASCIST? The Governance of the Question | Knowing God

Pingback: WAS LE CORBUSIER A FASCIST? The Mechanics of the Question | Knowing God

Pingback: WAS LE CORBUSIER A FASCIST? The Structure of the Question | Knowing God

Pingback: WAS LE CORBUSIER A FASCIST? The Land Where The Question Is Heard | Knowing God

Pingback: WAS LE CORBUSIER A FASCIST? The Mystery of the Question | Knowing God

Pingback: WAS LE CORBUSIER A FASCIST? Well, Yes, But… | Knowing God

Pingback: WAS LE CORBUSIER A FASCIST? A Question of Assertion or Play? | Knowing God

Pingback: WAS LE CORBUSIER A FASCIST? Our Current Common Conditions | Knowing God

Pingback: WAS LE CORBUSIER A FASCIST? Conclusion and Index | Knowing God