In my previous posts – links HERE, HERE, HERE, and HERE – I was telling a story. It is a story about stories, in that it was prompted by three French journalists telling us a story – namely, that the famous 20th century architect Le Corbusier was a Fascist. It is a personal story, in that I am repulsed by fascism but love Le Corbusier. It is a geo-political story, in that Corbusier was born and raised, quite actually, right in the middle space between French cosmopolitanism and German Nationalism. It is also, of course, a story, about Le Corbusier and his work. And, it is a story with multiple other stories folded up inside a story. I have told a few of those stories inside a story, which hopefully began to give a sense of why this blog series carries its title. Now I want to continue to tell more of those.

“All machinery is derived from nature, and is founded on the teaching and instruction of the revolution of the firmament. Let us but consider the connected revolutions of the sun, the moon, and the five planets, without the revolution of which, due to mechanism, we should not have had the alternation of day and night, nor the ripening of fruits. Thus, when our ancestors had seen that this was so, they took their models from nature, and by imitating them were led on by divine facts, until they perfected the contrivances which are so serviceable in our life. Some things, with a view to greater convenience, they worked out by means of machines and their revolutions, others by means of engines, and so, whatever they found to be useful for investigations, for the arts, and for established practices, they took care to improve step by step on scientific principles.”

– Vitruvius’, The Ten Books On Architecture, Book X, Ch.I. 4

Vitruvius was a Roman architect, and he wrote the first ever treatise on Architecture. To summarize him here, humanity’s machines imitate the turning of the heavens. To clarify, this is based on embodied sense of watching the heavens turn overhead. Of course, we wouldn’t think of machines that way anymore, because, as discussed in the previous three posts, our image of reality isn’t located from a position of sensed embodiment in the first place. To further expound, humanity’s machines were consciously of a lower scale and order than heaven’s lathe, which had authority over us. Our workings were, again, imitations, and we had to be taught by what was higher and greater. Also, the cycles nature determine the lives not of individual humans but of the entire community.

“1. I HAVE briefly set forth what I thought necessary about the principles of hoisting machines. In them two different things, unlike each other, work together, as elements of their motion and power, to produce these effects. One of them is the right line…the other is the circle…but in point of fact, neither rectilinear without circular motion, nor revolutions, without rectilinear motion, can accomplish the raising of loads. I will explain this, so that it may be understood.

2. As centres, axles are inserted into the sheaves, and these are fastened in the blocks; a rope carried over the sheaves, drawn straight down, and fastened to a windlass, causes the load to move upward from its place as the handspikes are turned. The pivots of this windlass, lying as centres in right lines in its socket- pieces, and the handspikes inserted in its holes, make the load rise when the ends of the windlass revolve in a circle like a lathe. Just so, when an iron lever is applied to a weight which a great many hands cannot move, with the fulcrum…lying as a centre in a right line under the lever, and with the tongue of the lever placed under the weight, one man’s strength, bearing down upon the head of it, heaves up the weight.”

– Vitruvius, The Ten Books On Architecture, Book X, Ch. III, 1., and 2.

To summarize, the elements of motion are the right line and the circle. The principles by which machines work are found in these two elements. And, machines hoist heavy loads with one or two people, which would otherwise require a much larger proportion of the community whose work is being accomplished. To expound, imagine a person standing at a right angle upon the straight line of the horizon, with the circular turning of the heavens overhead, and we get a sense of the cosmological significance of what’s being discussed here.

To give more of a sense of what we’re talking about, here are drawings of relatively ancient – though at the time very advanced – examples of such machines. They were used in the edification of the famous Cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore, otherwise affectionately known by Florentines simply as the “Duomo” (in reference to the dome). Just so my reader has an idea what we are looking at, the machine on your left was used to hoist a heavy load from the ground. The machine on your right was then used to move said heavy load laterally into place. What did these machines help to accomplish?

What appears here is a photo of the completed Florentine Duomo. It was built between 1296 and 1436 A.D. What I want to point out is that, despite being the largest dome every made up to that point in human history, and though without traditional Medieval buttresses along the exterior to carry weight, it doesn’t appear as a machine. Rather, it appears as an organic artifice made of earth and crafted by the human hand. And, that’s because it is. The machines help humans, scaffold the edification of the building, and then disappear. The machines are not what are to appear or take form. This is also evident on the interior, as seen, for example, HERE.

Also notable, the fact that it is actually a hexagon serves as a kind of archetypal example of how ancient domes were meant as mere human approximations and imitations of the spherical dome of heaven, rather than presuming to be copies or reproductions.

What appears here is the altar at Santa Maria del Fiore. What I want to draw attention to, however, is the stairs. They work to accomplish a similar function as the machines that raise the building. Namely, they work to hoist a load, though the load is a human person rather than a stone, and the weight is less. And still, like the rest of the building, they do not appear as a machine. Rather, they appear as organic artifice of the work of the human hand. The example of the Florentine Duomo, in this sense, was utterly normal for every human artifice prior to modernity.

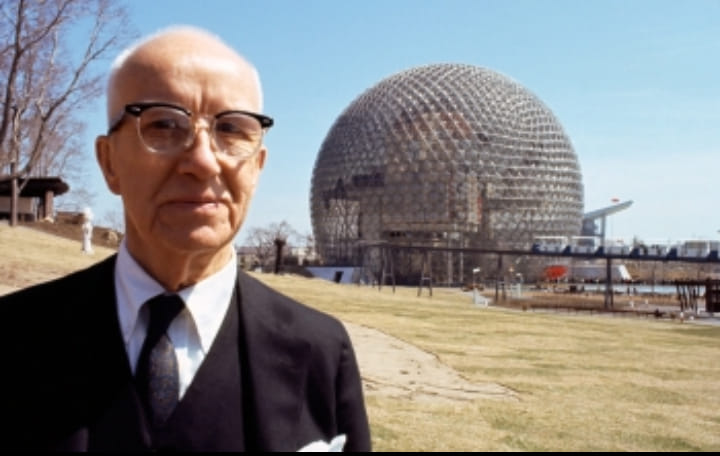

One major shift in human history from ancient to modern is from politics according to the words of community leaders – whether good or bad kings – to a conception of human society itself as a machine. The reason it’s anachronistic to refer to ancient political ideas as ideologies is because the whole point of an ideology is for it to be a “science of ideas” that presumes to, as with the power of a machine, control social outcomes at a scale far larger than that of the local community where ancient leaders previously held authority. And, our buildings tend to reflect and extend from the humanity who makes them. So, what appears here is Buckminster Fuller’s geodesic dome, of the mid 20th century. Notice that it’s no longer a “mere approximation” of the dome of heaven, and that it actually appears as a machine.

Part of what eventually developed over time with our conception of society as a machine was a vast set of mechanical apparatuses known as bureaucracy. Le Corbusier’s various city planning projects explicitly included massive “administration” buildings. Notably, they didn’t appear as machines, at least not in the same way as Buckey Fuller’s contraptions. Corbusier was more subtle than that, and more aware of and interested in referencing what is lost when moving forward, away from the body and the horizon (see previous posts, HERE, HERE, AND HERE).

He was also, however, interested in reconciling with the actuality of the conditions set before him. So, remember what Vitruvius took to be the elements of motion exhibited in machines? The right line and the circle. What was their function? To hoist loads upwards. What did they imitate? The turning of the heavens. Where society is conceived of and functions as a machine, then, Corbusier has human persons themselves move on a mechanical incline, along a series of circular and right-angle motions, upwards toward heaven.

The idea of a human person moving mechanically upwards towards heaven in reference the ancients use of machines to edify their buildings and communities was not at all atypical for Corbusier’s work. At Villa L Roche-Jeanneret, however, the motion was more of a grand, sweeping movement than a straight incline broken by tight, circular turns.

Ironically, as authority moved away from the organic voice, and work of human presence and was mechanized, individualism also appeared on the scene of our history. When society became a machine of monstrous scale, the person responded by refusing to get lost and became an individual authority. “We are not mere robots,” we say. Remember that Vitruvius’ point was that humans were “instructed” and taught by “the firmament.” What appears above is the individual person’s view as he or she ascends along the mechanical incline of the ramp that serves as the central “stair” at Villa Savoye. Was Corbusier depicting heavenly authority of the individual, or was he placing the modern person before and below a view of what teaches him or her? This, in effect, is a question faced by those on both the political left and right.

So, we have seen Corbusier tell stories of what it means to be a modern person. This means he has articulated the conditions of humans appearing and living in a modern world that is appearing to them. “Stories within stories” told of what this means include those of the “ground” of optical perspective, living on a globe rather than the earth, the death of the body and sensuality, and progress, optimism, and Idealism as governing images of modern life. We have now also seen that living in a modern world means living in, and even in some ways functioning as, a machine, at the scale both of larger society and of the individual. Later, I will further address how we might be able to see fascism in Corbusier’s response to these conditions of modern life, but, for now, I need to tell another “story within a story” in order to get a better picture of what was being responded to in the first place.

Pingback: WAS LE CORBUSIER A FASCIST? The Structure of the Question | Knowing God

Pingback: WAS LE CORBUSIER A FASCIST? The Land Where The Question Is Heard | Knowing God

Pingback: WAS LE CORBUSIER A FASCIST? The Mystery of the Question | Knowing God

Pingback: WAS LE CORBUSIER A FASCIST? Well, Yes, But… | Knowing God

Pingback: WAS LE CORBUSIER A FASCIST? A Question of Assertion or Play? | Knowing God

Pingback: WAS LE CORBUSIER A FASCIST? Our Current Common Conditions | Knowing God

Pingback: WAS LE CORBUSIER A FASCIST? Conclusion and Index | Knowing God