In my previous posts – links HERE, HERE, HERE, HERE, HERE, and HERE – I was telling a story. It is a story about stories, in that it was prompted by three French journalists telling us a story – namely, that the famous 20th century architect Le Corbusier was a Fascist. It is a personal story, in that I am repulsed by fascism but love Le Corbusier. It is a geo-political story, in that Corbusier was born and raised, quite actually, right in the middle space between French cosmopolitanism and German Nationalism. It is also, of course, a story, about Le Corbusier and his work. And, it is a story with multiple other stories folded up inside a story. I have told most of those stories inside a story, which hopefully began to give a sense of why this blog series carries its title. Now I want to continue to tell more of them.

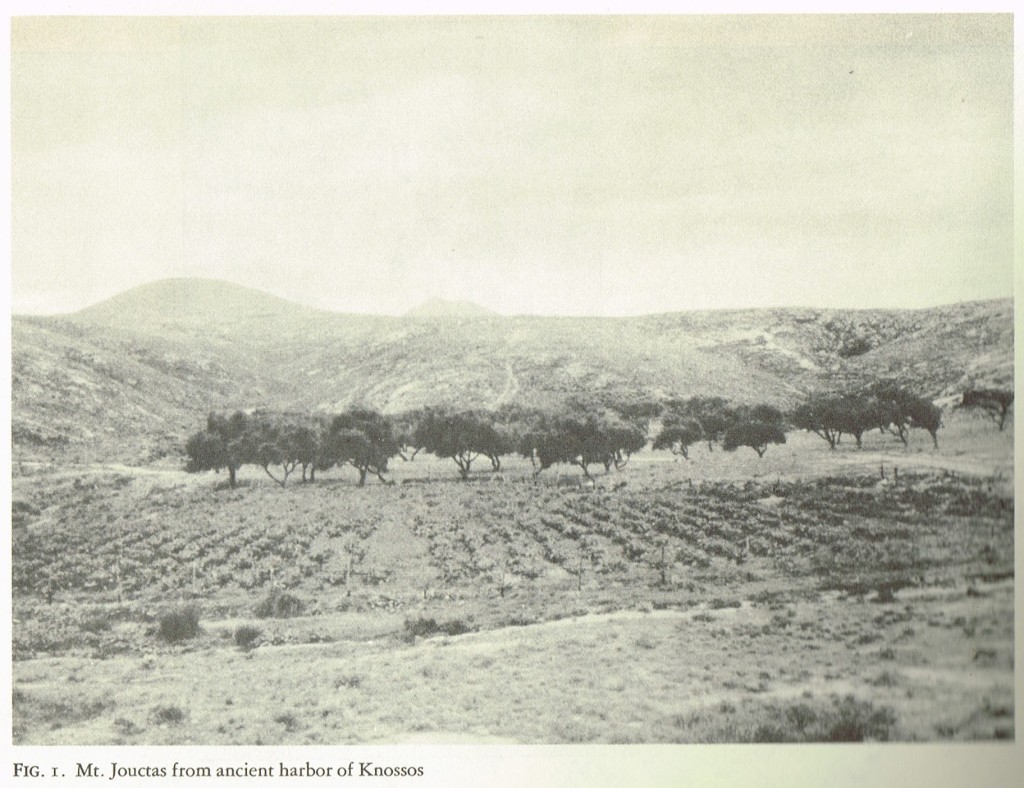

The above photograph is from Vincent Scully’s The Earth, The Temple, and the Gods: Greek Sacred Architecture. Scully refer to this as a “cleft mountain.” We’ve all heard the term “cleft,” but what exactly does it mean?

Cleft – “split; divided; a crack or crevice; an indentation between two parts…” – from:

from some free online dictionary, HERE

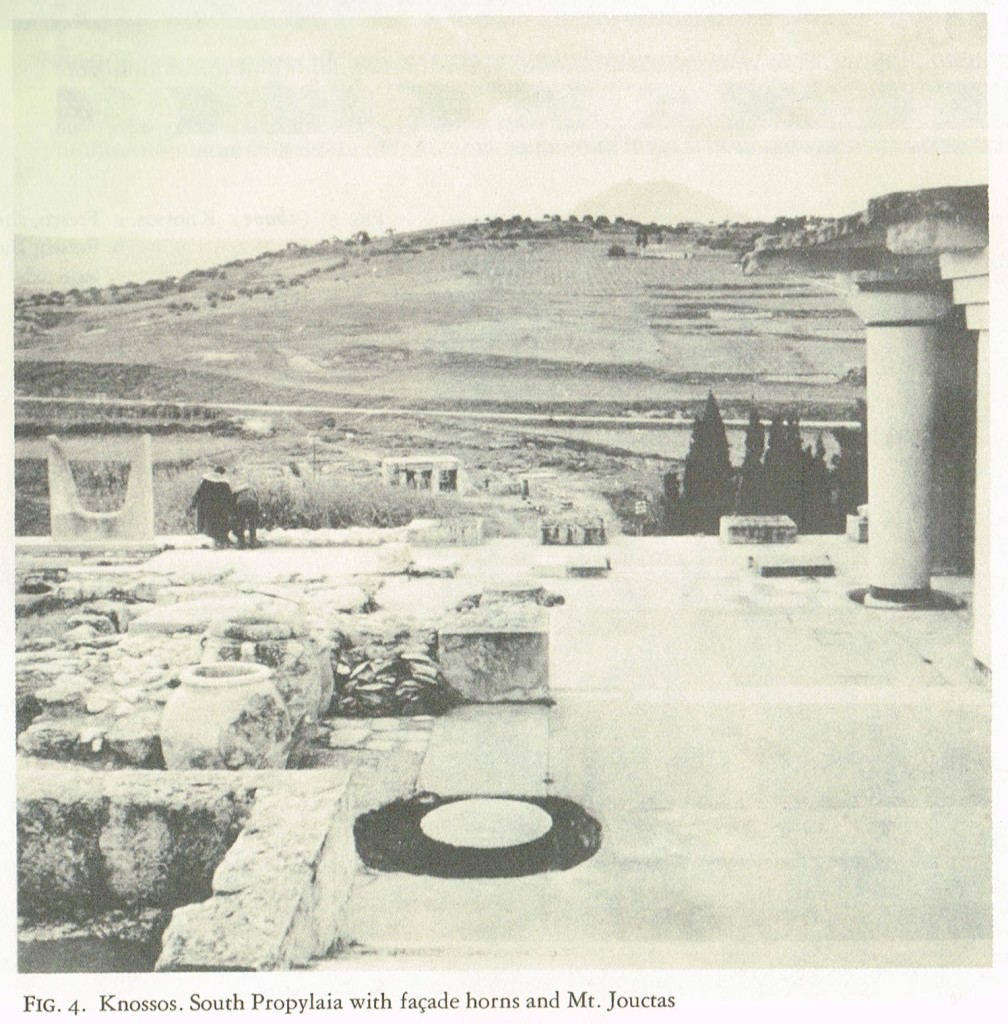

A propylaea is a monumental gateway that functioned as a portal between sacred and secular spaces. That is to say that, at the entrance to the sacred space of the Knossos palace complex, the community was faced with a view of a cleft mountain. Why would that be? The mountain presents an image of the earth, of which the building is made. The image of the cleft that opens to make way for the appearance of a mass of earth gives us a sense of what ancient stone masonry was about in ancient Greece. We see an opening emerging in a mass of dark and mysterious shadow. We see the Orphic piercing of weight and darkness with light through openings to make way for plastic forms to move towards a harmoniously ordered arrangement. Here, the arrangement is not only of architectural, cultural, and religious elements but of communal life. The community’s face turned towards a cleft mountain is their posture of veneration and worship of the earth goddess who gives them life from what lies hidden under her belly.

The image of bull horns on your left in the picture functions in much the same way: as an image of strength, virility, life, abundance, and as a symbol of the provision and support of Demeter.

Of particular note, Mt. Jouctus hasn’t moved in 4,000 years (at least). The Knossos Palace complex was placed, oriented, and built in relation to that specific mountain. To be somewhere else would be for Knossos to be a different building, housing a different community, with a completely different meaning.

Every single sacred site in ancient and classical Greece was oriented to a cleft mountain in a similar way. Knossos was not a one-off.

Le Corbusier’s Villa Savoye, however – see multiple previous posts, but especially “Moving Around The Question,” HERE – can essentially be built anywhere. Though his projects typically respond to the site in some particular way, part of what Corbusier is doing with his work is articulating, making sense of, and commenting on the nature of our modern environment and the conditions in which modern people find themselves. That Villa Savoye belongs and could be built anywhere, and thus nowhere, renders it a particularly modern home. To be modern is to be homeless, to be divorced from the land, to be an alien in exile.

Remember – as discussed in the first post of series, The Ground of the Question (HERE) – that Corbusier, in his work, is also asking questions about “the ground.” We discussed how the ground is a construct that shapes human perception. It has also become a construct that dominates our perception so widely as to go unrecognized as such. In Corbusier’s work, we see him observing that modern persons stand and appear upon a ground rather than the earth.

We also discussed – in “The Governance of the Question” (HERE) – that and how optimism, progress, and Idealism constituted a governing image of his early work. In the sense that it was what made his early work appear and moved it into existence, that image of progress functioned as a kind of “ground.” Upon it, his work stood or fell. Upon it, we were able to see and perceive his work and its meaning. The abstraction of the ground was the ground upon which the Ideal of Utopia was to be built. Through the course of two World Wars, we saw Corbusier’s work change. I will get into some of the specifics of how that’s the case in my next post. For now, we need to note that the design for Le Corbusier’s Monastery at La Tourette, near Lyon, France, began in 1953.

As Le Corbusier was working on each of his projects, he had an aphoristic saying that partly helped guide what he was doing. At La Tourette, that saying was, “The ground is falling away.”

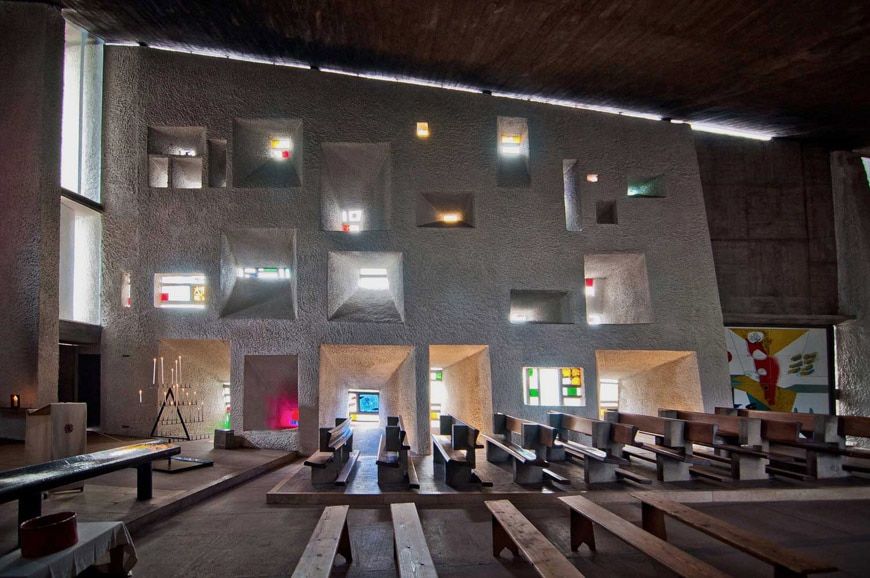

As one enters through the propylaea between parking lot and monastery, they see no cleft mountain. Only human edifice. As we move onto the sacred premises, “the ground” falls away underneath, as the building rises over it. The square has, in our history, long functioned a symbol of mother earth. One of the primary images that guides the language of the architecture here is a dark, mysterious shadow in the shape of a square, with space in a mass of darkness seemingly opened up from above by a piercing, white light. A photo of this was featured in a previous post of this series, “The Structure of The Question,” HERE.

If you look closely at the above photograph, you can see at least three cleft mountains subtly appearing along the horizon. One of them is very obviously on view while the community sits in the cafeteria eating and fellowshipping together. We can see in this photo of the exterior of La Tourette, HERE, that, as “the ground falls away,” the building opens to those cleft mountains, as they appear in the distance. Corbusier’s orientation of his building in relation to cleft mountains on the horizon at La Tourette was not a one-off.

From this photo, we can begin to get a sense of the story this chapel tells of relating with land and sky, earth and heaven. And, as at Knossos, this story is not just about the building but also, and especially, the community.

From this photo, get a sense of how the building is imagined as mass of carved-out earth, with light piercing through from above to give life.

I made this drawing when I visited Notre-Dame du Haut in Ronchamp. In the center of my drawing is a small sketch of the building’s plan view. The starfish shape that points in five directions doesn’t actually appear at the building. That is my diagrammatic key to the rest of my drawing. However, key to understanding my key is also knowing that, as you stand at that opening into the mass of the building, turn and face the horizon, what you see is cleft mountains. Well, with the exception of the rear of the building, where the water drain opens to the cistern. In that direction, you instead see bells, whose ringing call to worship pierces the soul with light.

In any case, my sketches of the building are right side up in my drawing. As I turned to face the horizon and draw the cleft mountains I saw from each position, I turned the drawing upside down. Thus, as in reality, the building and cleft mountains face and reflect one another in my drawing. Hence that particular quote from T.S. Eliot’s The Wasteland that I scribed at the bottom of my drawing.

Here, it becomes important to note that the concrete of the chapel at Ronchamp was made using stone aggregate taken directly and locally from the mountain on which the building arose.

So, if Corbusier saw “the ground” of modern life “falling away” after two World Wars, then what does it mean for these cleft mountains to appear at his most famous later projects? Namely, if his earlier work was built upon the grounds of optimism, progress, and Idealism, but if that ground “was falling away,” then what was left to build on? What we see Corbusier moving towards is building upon the earth. After all, when we covered over the earth with the ground, the earth never went anywhere.

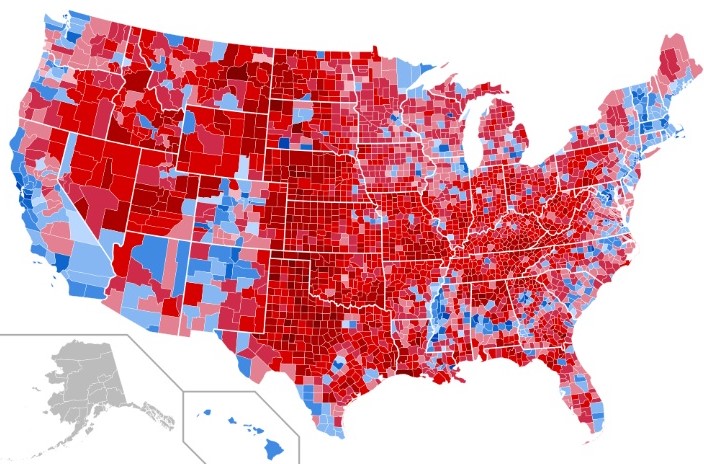

What if the earth even continued to shape modern persons and life, even as our vision for “progress” was built on something else? And even if we don’t recognize it? After all, for humans made of dirt and breath, is this not inevitable? Modern humans are shaped by a movement above and beyond the bounds of land and horizon – see “Moving Around the Question” HERE – but perhaps we can’t escape them. Why are our voting habits so shaped by how bound, or not, our way of life is to the land? Certainly we are shaped by the land, regardless of whether we are politically committed to left or right, conservative or liberal parties. American Christians’ voting commitments shifted parties from progressive to conservative not too long after Corbusier’s work changed, too.

So, we have seen Corbusier tell stories of what it means to be a modern person. This means he has articulated the conditions of humans appearing and living in a modern world that is appearing to them. “Stories within stories” told of what this means include those of the “ground” of optical perspective, living on a globe rather than the earth, the death of the body and sensuality, governance by Idealism and progress, individual movements according to the laws of mechanical motion, and being structurally “held together in tension.” We have now also seen him both telling us about our relationship with the land.

Neither the conservative nor liberal, right nor left, escapes any of these stories that shape the conditions of our environment. Later, I will address how and whether Corbusier responded to these conditions as a fascist, and, perhaps, to what degree. For now, I need to tell one last “story within a story” in order to get a better picture of what was being responded to in the first place.

Pingback: WAS LE CORBUSIER A FASCIST? The Mystery of the Question | Knowing God

Pingback: WAS LE CORBUSIER A FASCIST? Well, Yes, But… | Knowing God

Pingback: WAS LE CORBUSIER A FASCIST? A Question of Assertion or Play? | Knowing God

Pingback: WAS LE CORBUSIER A FASCIST? Our Current Common Conditions | Knowing God

Pingback: WAS LE CORBUSIER A FASCIST? Conclusion and Index | Knowing God